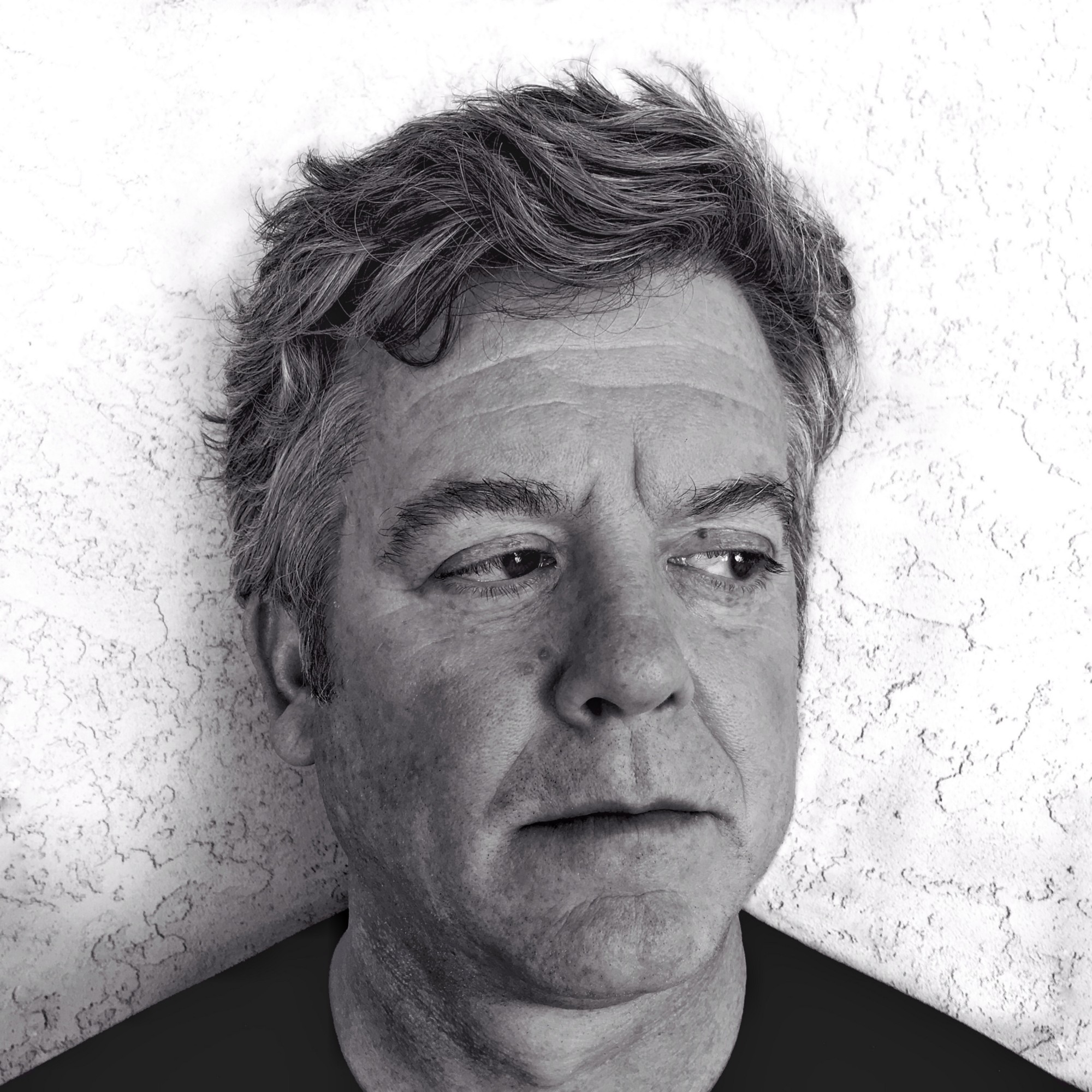

Design Manifestos: Shawn Keller of CW Keller and Associates

Shawn’s work embodies the shared vision of CW Keller and Associates. From modest beginnings, literally the basement of Charlie and Shawn Keller’s family home, CW Keller has continued to grow and evolve into one of the most technologically advanced fabrication shops in the US. The shop’s cornerstone is embracing the process, not just being experts in a material. According to Shawn, “the process unlocks the potentials of the materials.” To this end, the company has never been about responding to current trends, but instead innovates within its own expertise. From opening a custom furniture retail store in 1980, to purchasing its first CNC in 1995, to branching out into custom concrete formwork in 2011, Shawn has never been about staying put and settling into a niche. He loves challenges.

Prior to CW Keller, Shawn Keller spent ten years as a senior project manager for a Boston architectural firm, where he worked on the design and implementation of programs for a broad spectrum. He continually draws on that experience in his interaction with current clients and their architects, collaborating to find the best way to achieve each project’s design and budgetary goals. Shawn is a graduate of Syracuse University. Modelo spent some time learning about some of the challenges that Shawn takes on and the shared vision of CW Keller and Associates.

On becoming a fabricator

My father started CW Keller. Our firm started as a custom woodworking company and my dad started it in the basement of our house where my brother and I were growing up. It was coffee tables and dining room tables. He was the industrial arts teacher at Wilmington High School in Wilmington, Massachusetts and was doing this on the side. It got to a point where he could transition to making it a full-time job for himself, and moved it out of the house into a small shop in North Andover, Massachusetts. Over the course of the past 45 years he grew the business up as a commercial woodworking firm that grew up through doing residential and then some commercial. Then we got into retail in the 1980s and 1990s. Estée Lauder was our main client through that period. We were building Origins cosmetic stores for Estée Lauder on a national basis, which was a great run. Estée Lauder was interested in doing a much higher-end retail environment so we went through multiple iterations of their stores, building them out nationally every 4–5 years. Then they would renovate and do them all over again. What that did is essentially allowed us to grow the infrastructure of the firm to support that client.

Ultimately what happened is the retail market started to slow down pretty dramatically in the late 1990s. It put us in a position to re-evaluate where we were going to be as a company and get back into more commercial work in the Greater Boston area. The challenge that we faced as a fabricator is there were a lot of people in that space. Here to New York City, there are hundreds of woodworking companies that can do reception desks and wall panels and the things that we’d be bidding against. Margins get driven down and competition is pretty fierce. We saw the growth of our company as enjoying doing things that were the heart of harder projects. Contractors would start to come to us and say ‘we’ve got this project, but we’ve got this one piece that everyone else keeps saying no we’re not interested in doing that.’ That was the part that we loved doing. From 2000 through to today we have aggressively gone after the hardest stuff out there. What’s the most complex thing that people are doing? We had some lucky relationships that were created with firms here in Boston and Cambridge. Nader Tehrani, Mark Goulthorpe — designers who are really pushing the envelope of what could be done and forcing us to step up our game to be able to do those projects. It’s blossomed from there.

On discovering his voice as a fabricator

It started with the early relationships that we started to build. My background is in architecture and I went to Syracuse for undergrad. Then I came back to the Boston area and worked as an architect in Boston for about ten years. What that helped me do was sit on that side of the table: design team with client with general contractor. What are the issues that they face in getting a project designed and budgeted and under construction? I was able to take the knowledge that I had living in the architecture-side of the business and start to apply it to how we approached our relationships with architects and general contractors. I knew what meeting they had just come out of before they came to meet with us and the issues that they had. Where we started to be more successful was in our ability to go to contractors and architects and say ‘we understand what you’re trying to do here, we see the drawings, we understand the goal and we’re going to bring a design-sensibility to helping you figure out how to build it.’

That was helpful in building relationships with a lot of architecture firms. We became a go-to team for them to be able to say, ‘before we go to our client, we’ve designed this thing, can you give us feedback? We’re thinking the budget for should be x, but we don’t want to design it, put it into a set of drawings and have the budget come back twice that.’ We developed a very collaborative relationship with the firms up here and then extended into New York by being a collaborator in feedback of concept. That allowed us to grow what are now the fastest growing parts of our business: our engineering team and our design team. We’ve gone from being a fabricator that was 80% production (guys on the shop floor building and using machinery, a handful of engineers and project managers) to essentially 50/50. We’re 20 engineers, design engineers and project managers and 22 fabricators on the shop floor. We’re trying to straddle that world between design and fabrication by building our engineering team to support the design side.

On specific principles he strives to adhere to

Profitability as a starting point. We believe strongly in transparency. We’re often asked to get involved with projects where the general contractor will say ‘we’ve talked to all these other people and no one can do this. Who’s your competition? Who else can do this?’ Our feeling in many cases is there isn’t a lot of others doing the things that we’re doing. The challenge we face is that the industry in many cases is still stuck in a mindset of ‘as a client I need to see 3 competitive bids for me to feel comfortable picking CW Keller as the fabricator.’ Often there is no one else who’s going to bid it. Or, bids may come in but they’re so apples to oranges that it’s hard for people to make decisions. One of the things that we’ve really tried to strive for is transparency of cost. We are open and willing to provide our clients with full documentation of the cost to build something. Here are our hourly rates, here are the profit margins that we’re trying to achieve and here are our engineering hours that we’re estimating. We’ve found that we’re able to start really changing the dynamic of how we work with our clients. We have architects that we’ve worked with, STUDIOS is a great example. They have offices in D.C., New York and San Francisco and we’ve been working with them for ten years. They have a track record now of working with us in this model, where they’ll specify us for a part of a project, knowing that we’re willing to provide them and their client with that level of transparency. And there’s a level of trust that’s been built up over a history of ten years of projects. It’s the only way we’ve been able to figure out how to work more successfully in projects that are so complex that there’s tons of risk associated with them.

On the evolution of his role

The evolution began with retail starting to go away and being an organization very geared towards: copy, paste, repeat. When we started to move back into the commercial and residential markets, everything is a one-off. You have to be a bit more flexible in building something once and you’ve got to get it right the first time. Then you’re going to go on and do something completely different. Where with retail, you’re going to build the same store fixture 40 times. Project management comes pretty simply, you just click a button and the drawings are there.

Now, we’re a custom woodworking company but we’re starting to get involved in the world of concrete. How do we get involved in pre-cast-in-place concrete projects? We’re starting to take things that we know how to do and figuring out how to step into an industry where we have no idea what to do. We’re figuring out ways to collaborate with people in those other industries to educate ourselves and go through steep learning curves. This evolution has been possible by changing the structure of our company and growing that engineering and project management component allowing us to be a lot more agile in how we approached the variety of projects that we do.

The opportunity for us is taking what we know how to do as a custom fabricator doing very complex wood-related projects. How do we apply that to steel fabrication? We’re not a steel fabricator but we have an incredibly robust engineering team, some come from a steel background. We’re strong at 3D modeling and we are speeding up the modeling process by hiring people who just write code or just write scripts to automate processes. If you tell them what the steel fabricator’s going to need, they can start to automate modeling processes to make it very robust to provide a metal fabricator (who might be weak on engineering, but strong on machinery and equipment capabilities) where we can step in and be their engineering team. The same thing applies for concrete form systems. Now that we understand how concrete forms work, we can apply those same strategies to build a concrete form system to cast the canopies that we’ve done here in Boston, the Miami Science Museum and Gulf Stream Tank. We are working for the lead engineer for the Sixth Street Trestle, which is a ¾ of a mile long bridge in Los Angeles that’s been designed and the team’s now trying to figure out how to build a form system for this very complex bridge structure. Our team has been engaged to help them figure that out and the robustness of our modeling and engineering team allows us to step into those different markets. It’s been taking a company that was based around millwork fabrication and seeing how we can expand it into these other markets.

On recent projects that represent the firm’s unique approach

There are 2 concrete canopies in front of the aquarium in Boston, called the Harbor Park Pavilion. That was our first large scale cast-in-place concrete project. We were doing a lot of work for Turner Construction and Utile Inc. was the design architect. The canopies had been designed. They’re double-curved concrete as cast-in-place. There’s no form system that exists in the marketplace to do double-curved cast-in-place concrete. Turner owned the project and a couple Project Managers reached out to us and said ‘we know you don’t do this, but can you come to a meeting with us, the architect, the structural engineer and the concrete team? Just listen to what we’re trying to do. Right now the plan is the concrete team is just going to ship hundreds of sheets of plywood to the job site, the architect is going to plot on paper sections through the canopy that’s 40-feet-wide. They’re going to tape them to the plywood and cut them out by hand and try to build a form-system on the job site. We just don’t think that’s the right way to do it.’

The strength of our company is CNC, we have large-scale CNC machines that are very good at cutting out very complex shapes that come out of the fabrication models of plywood or other materials. Having that infrastructure and equipment that we use to build other things was pretty simple once we realized what the team needed. It was pretty straightforward for us to build a form-system for them, send it to the job site as a kit of parts and have them assemble it on what they’re traditionally using for cast-in-place concrete. We used the analogy of you’re making a cupcake and you have your cupcake pan, which is a metal pan. You have a little piece of paper that has all the ridges on it. You fill that piece of paper with cupcake batter and you put it in this metal pan. You pull the cupcake out and it has the little ridges on the edge. We’re the paper in the system.

There are international companies that build form systems for concrete and they’ve figured out 98% of what you need to do in cast-in-place concrete. But what they don’t do is deal with double curvature or complex geometry. They like to do straight walls, flat floors, facets, maybe a single curve but as soon as you try to do a twisted surface, there’s no product available to do that. We just become that very thin interstitial layer between standard form systems and that complex surface that an architect’s trying to achieve. Harbor Park became a great opportunity for us because it was immediately published as ‘look at this project and what people were able to do. This is how they did it.’

The phone just started ringing. Within a year we had the contract to do the engineering and form system for the main aquarium tank for the Miami Science Museum. The best way to describe it as is the aquarium that we have in Boston. Six of those will fit in this one tank in Miami. From a scale-standpoint it was giant. The design was done by Grimshaw in New York and it’s essentially a martini glass shape that’s rotated. It’s three-stories in the air and supported on 6 cast-in-place concrete legs. You actually walk underneath it. There’s a 32-foot-diameter clear acrylic oculus that you look up through to see the underside of the tank. Then it’s open air above. The general contractor on that project is the same general contractor on the Sixth Street Trestle out in Los Angeles. They’ve said ‘great job here, can you come look at this project out in LA?’ It’s allowed us to apply a lot of the same methodology in other projects as we’re using in concrete form systems.

On his design toolkit

Another influence for us has been how people like Mark Goulthorpe and Nader Tehrani have been using 3D modeling. That’s the direction they were going in their practices. Everyone was AutoCAD-based and everything was planned in elevation and section. They were some of the early adopters of 3D modeling software and we were doing a lot of work with them. We realized pretty quickly that we’d better be using the same software as they’re using or we’re going to get left behind. We can’t take a complex 3D surface and draw it in the software that we have because it’s like cutting a slice through an egg. Every slice is different. We had some projects that were great because they were very collaborative. In the C-Change project, Mark had a very robust team of engineers and modelers who were developing the 3D model of that project that our engineering team essentially got to shadow for about a year. We got educated from that team on how to do what they were doing and what software they were using.

We are exclusively Rhino-based as far as 3D modeling. We are on a trajectory to eliminate paper shop drawings within our facility probably in the next 18 months. Everyone on the shop floor will be interacting with Rhino models through laptops, instead of getting a 50 page pile of paper for whatever crazy thing they need to build. They’re going to open the Rhino model and just start interacting directly with it. We’re on a crusade to get our clients to not get shop drawings and we have companies, like STUDIOS, that have accepted that we will only submit to them a 3D model of the project. The other interesting part of 3D modeling is that it’s interesting to see architects designing spaces with the same 3D modeling software that we’re using. They’ll design an element using the software and give us the model and we’ll always ask if we can use the model for fabrication. 99/100 times they say no and we have to remodel it because they can’t assume the liability of us building off of what they drew. That’s something that we see architects and engineers starting to grapple with. If they’re going to put all this energy into creating a model of something that they want built, at some point we have to start to get them to accept the risk of ‘you drew it, we can build from it, your client’s going to pay us to model it all over again.’ Either engage us from the get-go to model it for you (which is what we’re doing in a lot of cases), or let us help you model it the first time with enough confidence that we can use it as a tool and not have to duplicate those efforts.

On the future of architecture in the next 5–10 years and the firm’s evolution

We have been adopting a lot of fabrication techniques that were developed for the automotive industry and the boat industry. If I start on the construction-side of things, the concrete industry from a global scale is ripe for a huge disruption in how things are done. The industry is still based on the premise that you’re going to flood a job site with a tremendous amount of manpower and fabricate form systems, hand-bend rebar, place it all by hand and cast-concrete for structures. The ability to prefabricate concrete form systems, the same way the furniture industry has gone from shops like us building custom-wood desks to companies like office environments and these other larger companies building systems furniture. The systems furniture has the acoustic panels in it, it has the electrical in it and it shows up as a kit of parts. You have to put it together and you have a work station.

When we did the Miami project, we called our form system the ‘IKEA version’ of concrete forms because we didn’t assemble any of it in our facility. We manufacture very complex forms as kits of parts, each kit was probably 10–15 pieces that were all machined to only go together a certain way. There was a one-page document with no dimensions, no instructions, just an exploded view of how that piece went together. The premise of it was ‘I need to be able to give a semi-skilled workforce on a jobsite the information that they need to put together a very complex, double-curved structure together.’ They can’t cut it, they can’t modify it, they just have to put it together and trust that when they put the model together it’s going to create this very complex shape. In the concrete industry, we see it continuing to adopt means and methods for prefabrication of form systems. The other big side of that is that we have to get to a point where we can do localized manufacturing of components. We’re in New Hampshire. Working regionally it’s fine, flat-packing systems and putting them on trucks and shipping them to Miami is ok but it’s not the ideal situation. You have a lot of shipping costs associated with sending that much material to Miami. Building the form system for a ¾ of a mile long bridge in New Hampshire and sending it to Los Angeles is just not feasible.

The approach that we’re starting to take is partly us looking at localized temporary fabrication facilities. The technology and machinery has evolved enough. For the project in Los Angeles, we go in, rent a facility for 18 months, put two CNCs in the facility, hire local labor to operate those machines under our direction and do all the engineering in New Hampshire. We output information to the CNCs in Los Angeles and it’s not different than us sending the information to the CNC that is 50 ft away in our shop. We do all the fabrication at the job site or within a mile of it. This eliminates or reduces trucking dramatically. You’ve leased the equipment, you give it back and you move it to the next job site.

The other side as far as how our company’s going to evolve is going to be around strategies that accelerate the process of doing analysis of concept for clients. They’ve designed the inside of an auditorium in Atlanta as a project that we’re working on for the Alliance Theater. It’s a very sculptural interior for a 650-seat theater. They’ve designed it — it’s a beautiful rendering. The client loves it. We have to quickly be able to analyze that and give them feedback on cost so that they can very quickly iterate design to get that cost to align with the client’s budget. We’re building sophisticated tools around the Rhino platform and working with architects who are working in Rhino. These tools allow us to quickly analyze what they’ve modeled and give them robust feedback on cost, so that they can make the right decisions to move forward. Internally for us it’s growing those capabilities. Instead of it taking us four to six weeks to put a bid together of something that’s that complex, we can do it in 3–5 days.

On advice he would give his younger self

One of the things that we have recognized over the past few years is that we need to build the best team possible. We’re working on projects that are pushing the envelope of what can be done. In the past, we had a team and they were a great group of talented people, who were good at what we had been doing for 20 years. They were excellent at building retail store fixtures. What we tried to do was take those same people and get them to be good at modeling concrete form systems. Some of them got it and some of them just didn’t want to get on that bus and go in that direction. We struggled with how to evolve the company and try to keep everybody that we had on board, instead of making strategic decisions around the right team. The challenge is twofold: getting the right people and the right talent to be able to do that and being ok with having some people get off the bus.

The other is the analogy we use: combining craft. We’ve got men and women on the shop floor who are incredible craftsmen and craftswomen. They know how to build and put things together and they take a lot of pride in the quality and workmanship of things that we put out the door. They’ve been doing it for their careers. Now we also have mixed into that a younger, more diverse engineering team. The best way to describe the culture-clash that we have right now is we have 4 people who drive Priuses to the shop, and a parking lot full of pick-up trucks with camouflage on them and the John Deere logo. You’ve got this very diverse talent-base interacting with each other. If I had to go back and say something to me 10 years ago, it would be ‘you’ve got to get out in front of this. You’ve got to be figuring out ways to build a culture and a team that is going to collectively embrace this challenge because that’s been a fairly rocky path for the organization.’ Going too long with people who were disgruntled with the direction that the company was going and trying to convince them that they should come along as opposed to saying it’s ok, you would be better off somewhere else.