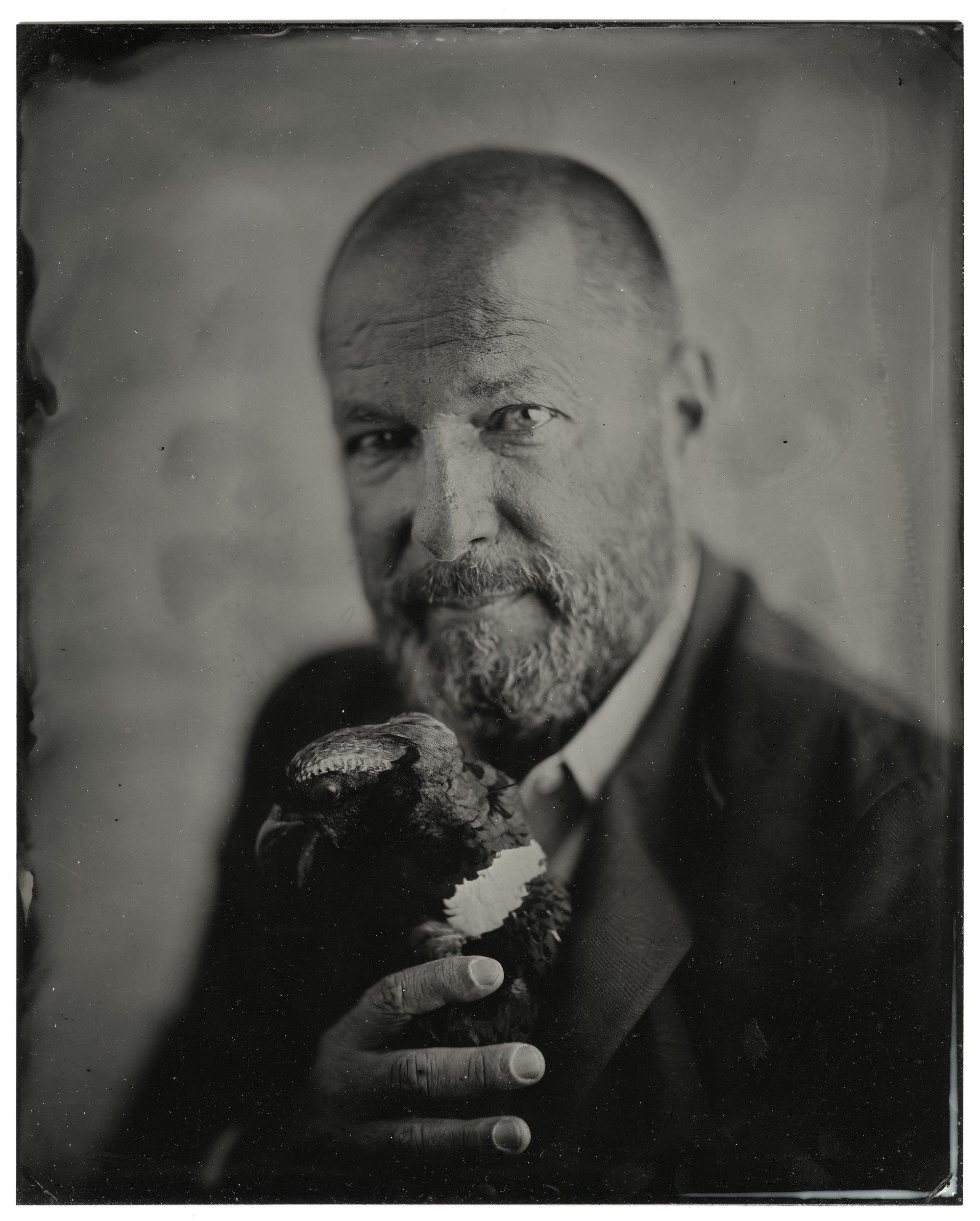

Design Manifestos: Alan Maskin of Olson Kundig

Alan Maskin is a principal and owner of Olson Kundig in Seattle, Washington. For over two decades, Alan has led building, exhibit and master planning projects, with a focus on museum architecture and interiors, exhibition design and installation design. His portfolio is focused on the public realm and his projects are visited by hundreds of thousands of people. Currently, he is designing the new Kindermuseum at the Jewish Museum of Berlin; an 80,000 square foot park inspired by an Aesop’s fable on the rooftop of a building in Korea; and a new cyber defense operations center at Microsoft. Modelo spent some time learning about Alan’s journey through the profession and about the evolution of his role at Olson Kundig.

On becoming an architect

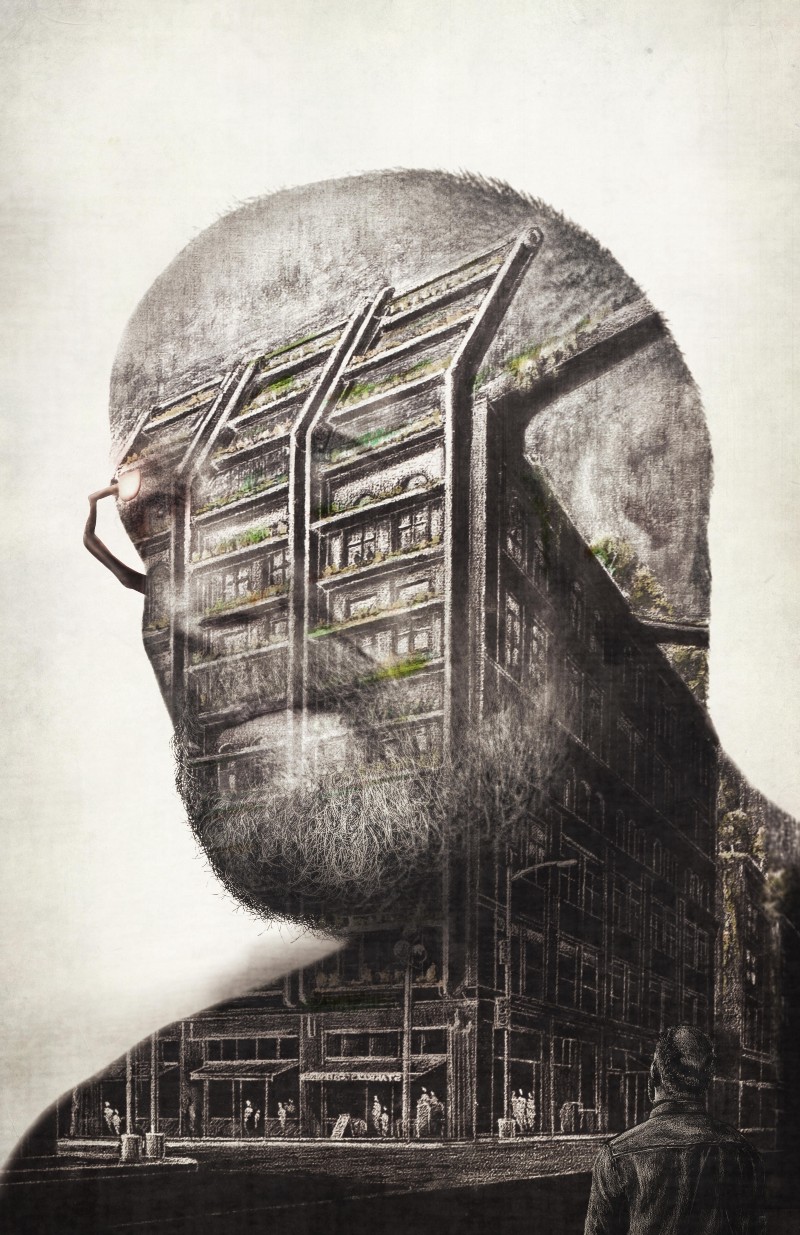

I became an architect because I love to draw. Years before I went to architecture school I saw a series of architectural section perspective drawings at a gallery in Manhattan and my mind was blown. I decided I wanted a job where I could draw every day, and I still draw every day. Around that time, I was accepted to a summer program at Harvard that is designed to help you decide if you want to become an architect. During that summer intensive, I realized the conceptual potential of buildings based on ideas. It hadn’t dawned on me that architecture could also be based on theory, hypothesis, and experimentation. That was all it took to get me fired up.

On discovering his voice as a designer

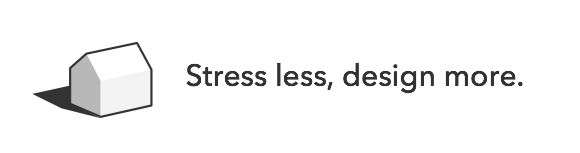

The beauty of this profession is that if you choose to, and play your cards right, you can practice for a very long time. The notion of a design voice exists in an evolving continuum if you are currently practicing — a lineage that seems to make more sense in retrospect when I see the spine that holds together much of what was created. That said, I’m more excited about how one’s design output can change and build. If I were to draw a line in the sand today, I’d say that I am fascinated by the role of provocations. Architects (proportionally speaking) deal with external provocations most of the time. A client hires you to solve their problem(s) and we are almost chromosomally wired in our DNA to move to solve them. Artists (again, proportionally speaking) internally provoke themselves. They wake up in the morning with a burning desire to make this thing that is in their heads. I’ve been making work in recent years that does both. A real project that was built for a client also became a fairytale, a conceptual urban plan, a fictional film, and a graphic novel. Oddly, someone saw it and is curious to discuss it as a real project in a new form. This duality of provocations has become a new way for me to make work in a series but, more importantly (to me at least), it provides a radically different way to look at and critique my own ideas.

I’m fortunate to make museums and museum experiences for a living. While I loved discovering Scarpa’s museum and exhibit designs when I was in architecture school―and a few years ago I was really impressed with The Art of Scent installation at MAD by Diller Scofidio and Renfro―I have mostly been inspired by museums made by people who are not usually in the business of museum making. The City Museum by artist Bob Cassilly was a big influence, as was The Museum of Jurassic Technology in Los Angeles by David Hildebrand Wilson. In a few weeks, I’m heading out to see the Library of Water in Stykkishólmur, Iceland, by writer and visual artist Roni Horn and currently I’m reading about the Museum of Innocence in Istanbul by writer Orhan Pamuk. Circling back to the previous question, I believe each of these projects was “self-provoked” by the creators of these four museums, so there is a pattern in the types of museums that speak to me and that has shifted my thinking.

On joining Olson Kundig

In my early twenties, I was an art teacher at the first federally funded on -site daycare center in the United States, located in Boston. The father of one of my students was an architect and I asked his advice about this idea I had to study architecture. He told me to do three things: move to Seattle to study at the University of Washington; once at UW, study with professor Astra Zarina, who he said had created the best foreign study program for architecture in the world; and get a job at Olson Walker Architects, the firm he felt was doing the best design work in Seattle. I did everything he told me to do, and he was right in every instance. Olson Walker has had several names over the past five decades, and now it is Olson Kundig, a firm I now own with four others.

My partner, Tom Kundig, and I often talk about what drew us to the firm and it tracked to the work that our founding partner, Jim Olson, was doing with artists in the Pacific Northwest. It was unlike anything else that others were doing and it became a great place to land.

On how his approach has evolved since he joined

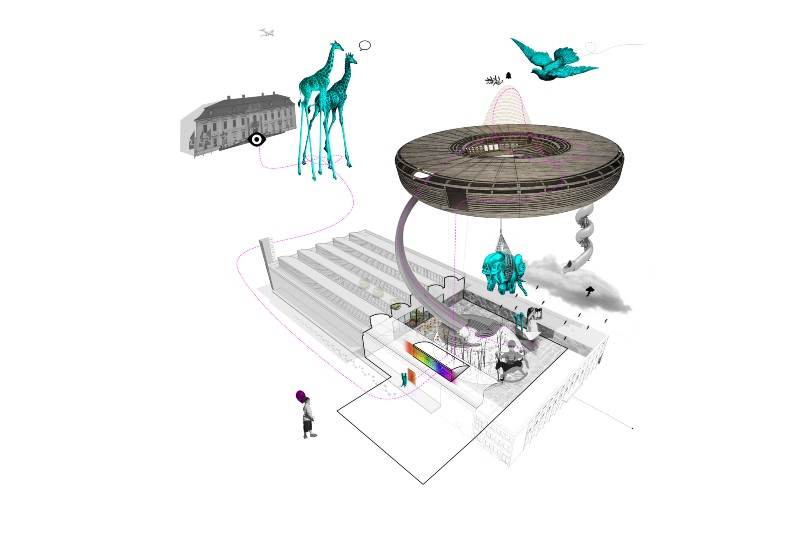

Twenty-four years ago I began as most intern architects do, moving along the slow arduous and lengthy path of becoming a generalist architect, and the firm is good at providing mentorship at that level. I worked on houses initially until I was asked to work with one of the owners on a small museum remodel. About four months into the project the scope blew up into a $12 million museum project which, at the time, was a very decent budget. I was hooked. In order to work on public projects versus private ones, I developed an aspect of exhibit design within the firm. What started as a start-up studio within Olson Kundig quickly became a full-fledged business and an important part of our portfolio. We were recently awarded first place in a museum design competition at the Jewish Museum of Berlin and we are completing a feasibility study for a world monument. We recently sent out drawings for our third rooftop park design―all of them are located in Korea―and we designed the Bezos Center for Innovation for Jeff and MacKenzie Bezos.

Many of these projects are interpretive―they merge some aspect of narrative with architecture. In many cases, there is a visceral line that demarcates the building design and the exhibit design―usually because they are created by separate firms. I design both, so I am always looking to blur the lines between these disciplines.

On specific principles he strives to adhere to

Olson Kundig has always been a firm that approaches work from a macro to micro perspective and we tend to only work on projects that allow us to design the project in its totality, right down to the smallest details. We have decades of experience working with some of the best fabricators in the construction industry and I have been obsessed with providing that level of craftsmanship to exhibit design. Conversely, there are makers in the exhibit realm that have fabrication techniques that I’ve used on building projects.

On his role at the firm

I am one of Olson Kundig’s five owners and each of us leads the majority of design projects at the firm. My focus has been on the public aspect of our portfolio and I have tried to find work that reaches large audiences. Two of my projects currently in design phases each have annual visitations of over 1.3 million people each. I’ve always skewed towards unconventional versions of what architects can create. Our first fictional film has been accepted to three film festivals this year, our first graphic novel was just published, and we have won two international design competitions this year―one for a museum in Berlin, and another for an illustrated fairy tale. The basis of what I make at Olson Kundig meanders between the real and the imagined.

On recent projects that represent his unique approach

For the past five decades, our core business has been architecture and it always will be, although my work can sometimes veer into new territories. We definitely come out of a Pacific Northwest tradition that is an outgrowth of Seattle’s long connections to Asian design influences, as a consequence of proximity and the history of our region, but also to the extraordinary northwest landscape. Wood has always been a favorite material for the firm, particularly as it is has become more and more of a renewable resource. As mentioned, building craft has also always been a big thing for us and we have become known for our attention to detail.

Perhaps the most innovative work that has come out of our firm has been our kinetic portfolio. Almost twenty years ago I worked with an unusual exhibit fabricator named Phil Turner who helped me solve some difficult challenges on projects. I set him up with my partner, Tom Kundig, who wanted to design an enormous steel and glass wall for a cabin in Idaho that could completely open with a turn of the wheel. Phil helped solve that challenge and, over the past twenty years, he has helped the firm build a portfolio of dozens of projects that make our structures adaptable through engineered kinetics. Phil is in his mid-seventies now but he is remarkably young at heart. It’s thrilling to see our young architects sitting at his desk learning to solve kinetic challenges of the future.

On his design toolkit

I always start by scribbling, usually on an early morning commuter ferry boat that takes me to Seattle. When I get to the office, the sketches are then shared with project teams that move them into the digital realm and a 3D digital model is created. We study the 3D views on the computer and often print them to sketch over, as the model becomes more and more defined. For a recent staircase design that would have been too difficult to replicate by hand, our digital model was sent to a 3D printer to create a large model. The results were thrilling―the complex geometries rendered beautifully, right down to the bolts on the I-beams.

On the state of design software today

Last year, I had the good fortune to attend the Future of Storytelling Conference on Staten Island. The conference focuses on variations of storytelling techniques and last year the experimentation of digital tools was a big piece of what was shared―hardware, software and digital tech―much of which seemed to have been laying dormant for decades. For instance, virtual and augmented reality, 360-film making, and holograms were all represented by projects made by creative developers who were given the new tools to see what they might make. There were 360-films you could walk into and 3D drawings where you could draw while walking into and through your drawings in real time. On one project you could fly over Manhattan―flapping your wings in any direction you chose―while flying through skyscrapers and zooming in and out of streets. It was clearly the dawn of a new era and the implications for designers are profound. At Olson Kundig we have begun using our digital architectural models and using virtual reality headgear to allow clients to step into their projects, even in the early concept phases, and walk around to see how it feels to them with fantastic results.

On the future of architecture in the next 5–10 years

The tools I just mentioned above will have a huge impact on the design industry as they not only change the ways we can perceive and experience design ideas but, more importantly, they change the way we see. I cannot underscore how profound these changes are, or how exciting and fun it will be to develop new ways to use them.

Aside from the tech tools, the biggest change in our industry will likely be related to project teams as more and more unusual partners from other disciplines are added to solve problems. I created an experimental R&D studio at Olson Kundig called [storefront] that was a public experiment in collaboration. We created 18 installations and events with community partners based on the question, What can we do together that we cannot do apart?The resulting design solutions became a study in design synthesis, as we only had one month and a budget of $1,500 to create each project with partners from our community.

On advice he would give himself

Given the choice of either being the tortoise or the hare, always choose the tortoise. Play the long game. Sit down each year and write down your immediate goals and your long-term ones. Paint a picture in your head, as fully rendered as you can imagine, of the projects you hope to make this year, next year, in five years, and in ten years. Work hard―constantly, relentlessly and consistently. Accept the idea that designers can’t quit, that you are in it for all the days you have left.