Design Manifestos: Kevin Kudo-King of Olson Kundig

Kevin Kudo-King began his career and nineteen-year tenure at Olson Kundig in Seattle, Washington as an intern architect and was named an associate in 2004, a principal in 2010 and an owner in 2015. Kevin works across a broad range of project types including private residences, museums, resorts, and mixed-use and institutional design. His projects extend from the firm’s home base in Seattle to work across the nation and around the world such as India, Mexico and Taiwan to Costa Rica, Europe and Australia. In addition to design leadership on projects, Kevin oversees Olson Kundig’s marketing and business development initiatives and serves in a leadership role on the board of trustees of Artist Trust, an organization that supports artists in Washington State. Modelo spent some time learning about Kevin’s professional journey as an architect and about discovering his voice as a designer.

On becoming an architect

I had an interest in sketching and building things from a very young age. I can still remember drawing sections of airplanes and structures and simply imagining how people might exist inside of them―it really interested me. Remarkably, I see the same thing with my own kids today, so architecture might be in their destinies too.

By the time I reached high school, I knew I wanted to be an architect and decided to attend the University of Arizona in Tucson. It’s a great place to learn about architecture because you can’t ignore the desert. It tells you what it wants and what it needs from you to build there.

On discovering his voice as a young designer

I developed my design voice in Arizona, when I would go out into the desert and basically think about what it means to be there and how humans can exist in that extreme environment. In order to do so, you need to build thick concrete or heavy walls; you need to dig down in the earth where it’s cool; you need shade. The light is so strong and dramatic, and there are inspiring views of the surrounding desert, mountains, and hills that need to be considered along with solar orientation as you design.

My education in Arizona really pushed me to think about “place” beyond the actual physical place, which is so important―it encouraged me to think about what it feels like to be in a particular location on a spiritual level. That philosophy guided my interest early on. It took a couple years in school―this was the 1990s―to wade through the external influences of the moment in order to focus on concepts that were more timeless. Some early influences for me were the Salk Institute by Louis Kahn and the work of Luis Barragán.

I joined Olson Kundig directly out of school. It was the place I wanted to work. Prior to that, I had spent a lot of time in the shop and had started making furniture out of steel. I had also worked in construction, which I feel all architects should do. I ended up at Olson Kundig because I valued the firm’s focus on materiality and the cornerstone principles of craft, site context and integration with nature. Olson Kundig was known for interweaving materials and details in a fashion similar to masters like Carlos Scarpa; they allowed the hands of the craftsperson to be expressed in their projects and celebrated the collaboration with the builder as part of the design process. This foundation was instrumental in allowing me to discover my own voice.

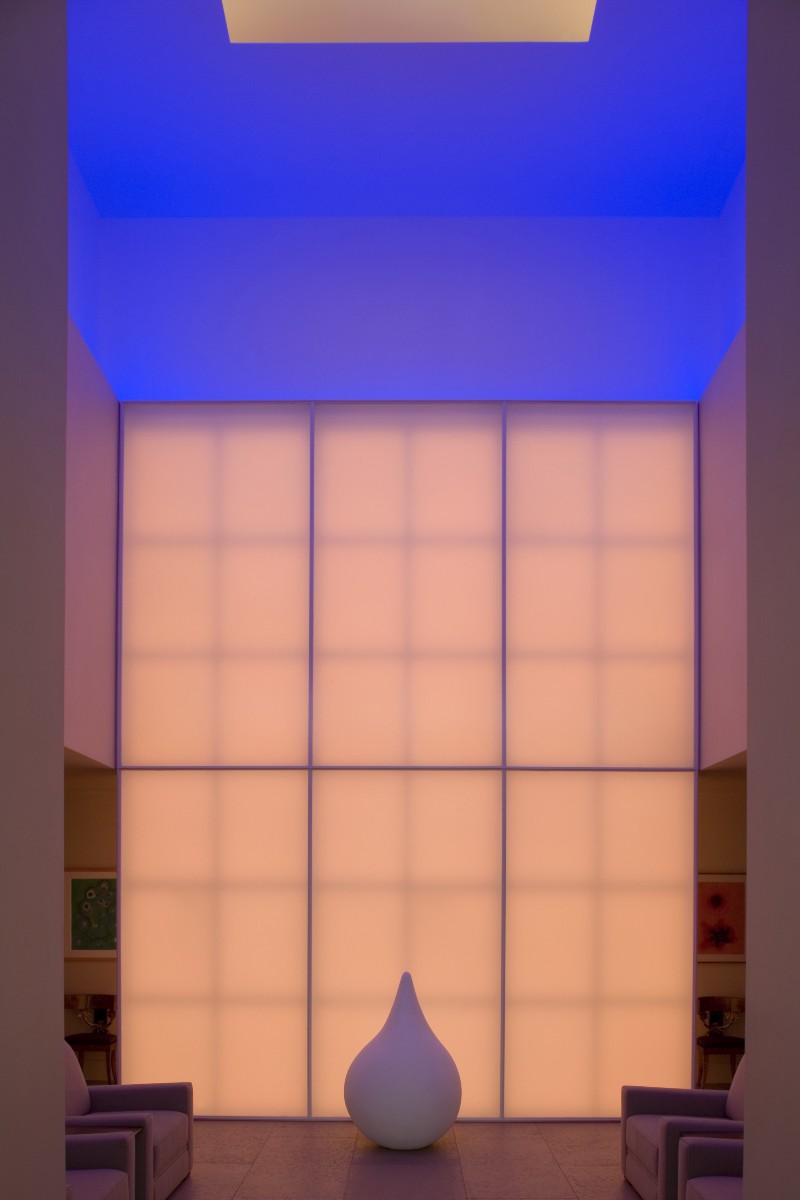

The development of my architectural voice was also rooted in the firm’s focus on the integration of art and architecture. I was introduced to the work of James Turrell and later worked with him on one of our houses. I will never forget being in a dark room with him at 5:30 in the morning while he adjusted the light in one of his pieces―it felt like I was inside of a painting, as it was being painted. We’ve done work with Richard Serra, too, and his sculptures have also influenced me. Although we haven’t worked with Hiroshi Sugimoto, I have seen his photos and pieces during trips to Japan and they are really amazing―they’re about capturing these perfect, abstract moments in time, which is what architecture can do, too.

My wife is from Japan, so we go there every year and have done so since 1997. That has been a huge influence on me not only because of the architecture and craft but also because of the experiential aspects of how things unfold in Japanese architecture and gardens.

On joining Olson Kundig

In school, we were taught to do everything ourselves. When you get out into the real world, however, you realize that it’s actually a team effort. At Olson Kundig, collaboration is especially important. At our practice, we work closely with builders, craftspeople, and artists.

When you get out of school, it hits home that architecture is a service profession, especially in the work that we do which focuses on residential architecture. I find residential design to be exceptionally fulfilling because people are coming to you to fulfill their personal dream of building their own home. It’s rewarding to see them moved by what we create together.

On specific principles he strives to adhere to

We work around the world, and in particular, I do a lot of international work. Right now, we have a project in Sydney that I’m working on with Tom Kundig and a project in London that I’m working on with Jim Olson. They are in two completely different places, but both of them are about creating architecture that fits into a specific context. By bringing our design values to a specific site and a client’s set of determinants our work continues to evolve.

We always prefer to work closely with the builder early in the design process and we value a very collaborative process during construction. We do not feel the design process ends when construction begins. Leaving enough latitude in the design to allow changes and contributions by the builder means we create something together that reflects all involved―it is something greater than we could have achieved separately or with a less collaborative attitude.

On his role at Olson Kundig

I focus a lot on residential and international work. I also work on hotels and cultural projects. For example, we recently completed a visitor center for the Bellevue Botanical Garden outside Seattle, Washington, and an art museum in Tacoma. It’s important to us that we remain a strong regionalist practice, which we have been since Jim founded the firm in 1966, even though we also practice nationally and internationally.

My concentration is project-focused. On some projects, I am the design lead, while on others I work in collaboration with Jim Olson or Tom Kundig. I also oversee our marketing department, who are a great group of folks and don’t really need much overseeing, but that is part of what I do.

On recent projects that represent his unique approach

We do have a unique approach―we believe in constantly reinventing ourselves. Every project is somewhat of a prototype because it needs to be about the place in which it is built, and about the people who it’s being built for, the combination of which is always completely unique.

One project I’m working on now is the Upper Garden at Leach Botanical Garden in Portland, Oregon. The property was owned by a couple who is well-known in the horticulturist world. They gave the property to the City of Portland in order to create a new public property at the west end of Portland for everyone to enjoy. The concept we proposed is inspired by traditional lath houses―in this case, we have designed a wooden lath structure and a building that floats inside of it. The buildings incorporate vegetated roofs and alpine roof gardens into the structure that are both architecture and exhibit. They are about education, experience, storytelling, and are beautiful structures.

I recently worked on the JW Marriott Los Cabos Beach Resort & Spa with Jim Olson, which opened last November. For that project, we wanted to create a resort focused on the horizon. When you enter the open-air lobby, you are greeted by views of the ocean and expansive infinity pools, creating the illusion of the ocean merging with the property. It is reminiscent of Sugimoto’s photographs of the horizon. We wanted to create an experience of unfolding―you enter the resort on a high elevation, then descend down into the earth, but eventually every path leads to you to the top of the dune, looking out over the ocean, where you feel like you’re practically at the end of the earth.

On his design toolkit

I came into the profession at a time when we were still taught to draft by hand, but we were also using early versions of AutoCAD, where you would type in all your commands. I’m glad I learned both. The computer is useful because you can study lots of variations and move things around easily, but its disadvantage is that you’re in this virtual world and you don’t really have a sense of scale.

In general, I start with hand sketches and drawings in a sketchbook, then I move to laying out the parts and pieces diagrammatically on the computer and, finally, I print those out and go back to hand drawing over the computer drawings. I move back and forth between the two because the act of putting pencil to paper allows you to feel the spaces you’re creating. We use physical models a lot and always have; I did the same on all my school projects as well. This also allows for a very direct tactile understanding of the project.

Nowadays, renderings and 3D modeling are amazing, but they still don’t take the place of being able to review a physical model. The client can hold it up, look inside, turn it around and understand the scheme at a more direct and tactile level. It is still less abstract than what the computer can produce.

On the state of software today

I feel the best tool an architect has is his or her imagination and training as a problem solver. We use Revit to produce construction drawings. My impression of it is that it’s not an extremely intuitive tool. What you can potentially do with it is amazing, but it has a very complex interface.

Ultimately our digital tools are going to become more intuitive and immersive, and they’re going to get better and better just like AutoCAD did. You used to have to type in commands to be able to draw, but then everything became more icon-based, more visual, and more intuitive. I’m sure Revit will head in that direction as well.

On the future of the industry and Olson Kundig in the next 5–10 years

Our practice is expanding and we recently dropped “Architects” from our name. We were previously “Olson Kundig Architects;” now we’re “Olson Kundig.” We do exhibit design, interior design, landscape architecture, furniture and gizmo design, and we even do videography. We use video to explain our kinetic work, which naturally lends itself to moving pictures. Video allows kinetic architecture to unfold in front of the viewer so they can truly experience it.

Phil Turner, who previously worked with us as a consultant, has been in-house since 2012, and he is simply a genius! Before he joined us he fabricated the kinetic designs we created. After he sold his company, he joined us to help with our kinetic designs. The profession of architecture is changing in that it has broadened and architects are finding new roles for themselves as designers of many things beyond buildings.

I also believe it’s become a smaller world. We’re doing work all over the world at the moment, and as architects based in the United States, we have a level of creativity that we can take elsewhere in the world. I hope that it will be easier and easier to do that. We could travel less when the digital technology and tools catch up; they work now, of course, but they are somewhat counterintuitive much like Revit is. I believe they will only get better and more immersive, and ultimately, less expensive and as the mass market embraces them.

For a long time now, people have been becoming more aware of sustainable design but I think it’s going to become more deeply embedded in our process more as architects. We have a member of staff solely focused on R&D and high-performance building technology―he ensures our projects are even more sustainable. We have always designed and built projects to last 100 years or more using local craftspeople and materials that respond passively to the climate. Now we’re going to take it one step further and be able to do the metrics and analytical work to make sure that they are aggressively energy efficient and incorporate the latest technology that carries them far into the future.

On advice he would give his younger self

This is a tough question. I look back and I realize I was very lucky to end up precisely where I wanted to be. However, if I consider whether that calculus class I took in college was useful, I would probably have to admit I didn’t really need to take it―even though I enjoyed it! In retrospect, I should have stuck with Spanish. We’re doing a lot of work in countries where people speak multiple languages. My wife speaks multiple languages, yet here I am, able to speak only marginal Spanish, some very bad Japanese, and only okay English!