Design Manifestos: Tom Nelson of BAR Architects

Tom Nelson is a Senior Associate at BAR Architects in San Francisco, California and a LEED Fellow with 30 years of professional architectural experience. His focus is on highly sustainably designed major projects for various higher education clients, cultural institutions and developers. Tom helped co-found the Los Angeles Chapter of the USGBC, and represents BAR as one of 50 firms in the US asked to participate in the A+D Sustainable Design Leaders Group.

As an experienced lead project designer, Tom pursues an architectural aesthetic that is bio-climatically responsive and creates humane space which is authentic in its context. He embraces technology and how, particularly the intersection of digital analysis and sustainable design, can enable more informed decision making early in the design process. Tom’s recent research has been focused on healthy building materials, identifying those which are appropriate for their use, have the least negative impact on the environment and human health, and are derived and manufactured in socially responsible ways. Modelo spent some time learning about Tom’s inspirations and current role at BAR Architects.

On becoming an architect

I have always loved to draw. Although I did not have an architectural influence as a child, there wasn’t an architect for 50 miles; I drew, painted, photographed and made prints of whatever I came across. I had a mentor, my high school art teacher who encouraged me to pursue art, which I did during my first year in college. My older brother had completed a fine arts degree a few years earlier. He was and is very talented, but upon graduation his interests went in a different direction. This experience left my father (the funder of my education) with an impression that an arts education would not be the best course. So I was given a choice; to follow my other older brother, the engineer or find something else that would provide a living wage after graduation. I chose architecture which at the time seemed the best sort of compromise — it would satisfy my desire for artistic expression and at least has kept me from living in a cold-water flat. Looking back, it was no compromise at all. The technical and aesthetic challenges have made it a lifelong learning experience and the rent has always gotten paid.

Technology fascinated me even before I knew what it meant to be an early adopter. I am always seeking out the newest thing, needing to understand how it works. I grew up around cars and trucks and learned mechanics almost through osmosis. All of these experiences shaped how I have grown in the profession. I put myself in the position to understand computers in the early 1980’s as they were just coming into use in firms. The computer is still the main tool I use and I continue to seek out the best (and often the newest) technologies to incorporate into my design process.

On discovering his voice as an architect

Early in my career I worked for large firms because I understood that I needed to gain the experience of putting a building together before designing one. I felt that large firms would give me access to the most varied types and scales and would provide the broadest experience. I was right about that, but finding my voice took longer than I expected. It started to happen with the introduction of sustainable design principles. I had a desire to base my designs on some fundamental meaning and purpose that rose beyond the financial success of the project.

It wasn’t until I was asked to be a sustainable design advocate in 1997 while at HOK’s LA office that I began to understand how to create meaning and purpose through the designs by allowing the work to be more than shelter or workspace and have a relationship with the environment. I was influenced by a number of people within HOK, like Bill O’Dell and Sandy Mendler who took on sustainable design at large scale very early in the movement. Their book “HOK’s Guidebook to Sustainable Design” caused a ripple of change though the industry. I was fortunate to contribute a case study of a straw bale office building in the 2nd Edition. The argument they made about the environmental degradation caused by buildings was so compelling that there was no denying that the profession had to respond by changing how buildings are designed and to base design on a climatic response, careful material choices, building less and using less. I thought of it as essentialism.

These ideas were reinforced by timely encounters with people like Paul Hawken and Jenine Benyus. Paul Hawken left me with a new way to look at commercial enterprise in the “Ecology of Commerce” and Jenine opened the possibilities of “Biomimicry” and how buildings can learn from and use natural systems. Jenine recommended an obscure book to me titled “The Extended Organism” the thesis of which was the idea that colonies of termites are in fact a single organism, demonstrated by the unified activities of these small blind insects maintaining their mounds with tremendously complex pathways and passive ventilation systems all while farming their own fungus gardens at the base of the mound which also functioned as the heat source for the community — a truly integrated design. It gave me hope for mankind. Rudofsky’s books “Architecture without Architects” and “Prodigious Builders” were very influential to me. They provided an understanding of how indigenous people responded to their environment with the technology they had and created beautiful authentic structures.

I always begin the design of a project with a natural principal like the buoyancy of air or some other law of thermodynamics as the form driver. The intention is to make a place for people and connect them to that place. I find that biophilic responses are real motivating factors for people to feel comfort and a sense of connection to the place.

On joining BAR Architects

Before joining BAR I was a lead designer and principal with Mithun in Seattle. I was with the firm for 9 years. A combination of a change in the project types Mithun was focused on and my own desire to leave the Pacific Northwest made me feel it was time to make a change. I had tried to settle in San Francisco at the outset of my career, but the economy at the time prevented it. This time it cooperated. I knew of BAR from their long reputation for great design in the Bay Area. When I met the leadership of BAR, I knew that these were people that I could work with and be a part of the firm’s continued growth. We had a common interest in producing great design and they were interested in increasing their capabilities in sustainable practices and digital technology. I was also interested in sharing the experience that I had gained and to use it on building types that I was not yet familiar with doing so. Those opportunities were presented by BAR.

Much of my career has been focused on Higher Education projects and at BAR I help lead the Higher Ed practice, but in keeping with my generalist roots, I participate in many project types in the office.

I had some experience in housing — the building type that currently makes up a majority of BAR’s work, but mastering a building type takes time. Fortunately there are a number of people in the firm who have made it their life’s work so there is no shortage of project examples and expert advice.

The main thing that has caused change is in learning how to approach developer driven housing project as high performance buildings. Most of the multi-family projects the firm takes on are urban infill projects. These projects present particular challenges. Many have only one exposed façade and are on sites that have a predetermined primary orientation. Usually, locating the building on the site would be a critical factor in building performance. Treatment of the building skin becomes a much more important effort. Another important element of high performance design is calculating the savings from energy savings and showing the payback to the owner in the discussion about capital investment in energy efficiency measures. Typically in developer financed projects in California, utility charges must be passed through to the tenants, so a cost savings for the developer or owner cannot be used to justify this investment. An argument can be made that the project may lease faster and have a higher valuation and this can lead to capital investment. Other approaches that may be appealing to developers are related to cost savings through faster construction schedules. This leads to research on different construction types such as prefabrication and cross laminated timber construction, both of which are highly sustainable while providing cost incentives to the developer.

On specific principles he strives to adhere to

Since the built environment has such a tremendous effect on the natural environment, I find the phrase “first do no harm” inspirational. As Bill McDonnough has said, we can’t just do less bad, we must do good. Our designs should attempt to be restorative, not just sustainable. I try to set the bar for building performance very high by using the Living Building Challenge imperatives as project goals even if they may not be achieved, aspirational goals are essential. Buildings should be bio-climatically responsive, create humane spaces, and be contextually appropriate. I always start with passive design principles with the intention of reducing the energy, water and material uses. As much as possible the building alone should do the work of maintaining a comfortable and healthy indoor environment through its orientation, shading, envelope insulation, without relying on mechanical systems.

On his role at BAR Architects

I lead the design efforts of different project types and help influence design overall. My primary responsibility is for Higher Education projects, but I enjoy working on any other project type as well, such as mixed use, housing, and civic projects. Because of my long experience with using technology in architecture, I also help lead our digital design group. This group investigates software and hardware, creates standards for their use, and determines training needs.

On projects that represent the firm’s unique approach

Our process is more integrative. We employ dialogue with people and technology. Our clients and consultants are critical members of the design team. This approach is essential to the integration of Architecture; Site/landscape, building interiors and systems. Technology is integrated into our process to assist our thought, test concepts and encourage us to push further and challenge ourselves. Each project is approached without any preconceived notion of a particular style. The site context, program requirements, climate, and budget are all fundamental drivers of the design. Once the team gains an understanding of these, the iterative process begins with many ideas explored, and tested. The desired result is a balanced approach that can be represented by a clear diagram — an arrangement that is easily understood, efficiently accommodate all of the project requirements and result in the creation of spaces and places that can lift the human spirit.

Law Winery, Paso Robles, CA

The project is a contemporary expression of a California working ranch that facilitates and demonstrates an efficient winemaking process while taking full advantage of its environs. Nestled into the hillside, this multi-level 23,778 square feet. winery fully engages visitors with a compelling tasting environment and showcases panoramic views of the estate’s coastal vineyards and topography.

Conceived to showcase the wines of this new, estate-grown brand, the winery features a production facility and tasting room that highlight the fractured shale geology of the hillside site, the climatic influences of sun and wind and the functional considerations of the winemaking process. Inspired by traditional agrarian compounds of the western United States, the design enables each element of the process to be expressed as a simple, distinct, and function-driven building form. The arrangement and connection of these core operational elements creates outdoor “rooms” providing programmed exterior work areas and places for visitors to relax and enjoy the views.

Creating a facility expressive of the winemaking philosophy was a primary design objective. The brand focuses on conveying the unique “terroir” through hand-crafted wines made with organically farmed fruit, passive management of the vineyard and gravity flow production processes. These objectives supported a design that intimately connects the building to the site and utilizes locally-sourced, durable materials to provide a healthy, long-lasting work environment.

Functional work-flow is organized to simplify the grape handling and winemaking process, allowing minimal intervention in the natural process and product. Equally important and reflecting the owners’ desire for a clean and contemporary style, the design provides visitors a refined, elegant and welcoming wine-tasting experience that captures the panoramic views of the estate’s vineyard to the north.

Connection to site and environs: The property’s slopes and topography were thoroughly studied to optimize the solar exposure, capture views and respond to local wind patterns. Building elements screen outdoor areas from the typical westerly afternoon wind. The visitor tasting room is positioned just south and below the site’s ridgeline, utilizing the natural topography to shield views of the buildings from a nearby road, while still presenting visitors an extraordinary 270-degree panorama and respecting the county’s ridgeline development restrictions. All of the wine storage and aging activities are located in subterranean rooms benched into the hillside. This location also provides protection and natural insulation from the hot summer days. The design approach not only minimizes the apparent size of the facility, but also allows exterior visitor parking within a courtyard that is contained on three sides by landscaped terrace or building walls.

A wine-tasting experience for all the senses: As guests arrive in the gravel-paved auto court, the Corten entry wall intentionally announces that a large portion of the facility was “cleft out” of the natural land-form. The small, cave-like entry door, recessed deep into the wall surface, hints at the subterranean barrel storage beyond and highlights the contrast between the solid and void that visitors will experience once they climb — via either the interior or exterior stairs– to the glass jewel-box tasting room twenty feet above. Surrounded on three sides by floor-to-ceiling glass and large sliding doors, which can remain open during a majority of the year, the simple but elegant tasting room embraces the casual comfort of a living room and offers indoor/outdoor terraces for a variety of entertaining options. Shaded by large roof overhangs, these areas heighten the connection to the surrounding landscape and provide year-round flexibility without costly indoor, conditioned space.

Creating efficient and healthy work environments: All production areas except the barrel storage rooms (where UV exposure is detrimental to the wine) have ample natural light, reducing the need for artificial illumination during normal work hours. Transfers of juice between crush, fermentation and aging areas utilize simple gravity flow, minimizing the need for electric pumps. State-of-the-art concrete fermentors provide a high thermal mass container, moderating temperature swings by absorbing heat generated during the conversion of sugar to alcohol. Within the large production spaces, high and low wall louvers allow exhausting of harmful CO2 gases produced during fermentation and passive night cooling of the spaces during most of the year.

Shaping the building to save energy: Building forms are organized to shade glazing from summer solar gain and admit warming winter sun. The roof shape is tuned for daylighting interior spaces. High performance low-e glazing insulates the interior and maximizes views and connection to nature. Roofs are oriented for PV production, with infrastructure in place for future plug-in arrays. The mass of the concrete structure works to exhaust heat using nighttime ventilation air and pre-cool the spaces. The barrel storage rooms are located below grade, harnessing the “Thermos Bottle” effect used to super-insulate the space and reduce energy use.

Extending the usefulness of water: Sloped roofs channel rainwater to a buried 15,000-gallon cistern, where it is stored and reused for landscape irrigation. A subsurface bioreactor recycles all winery process water for vineyard irrigation. Flat areas of green roof slow stormwater and allow evapotranspiration. Impervious paving is minimized. Xeriscape eliminates the need for ornamental irrigation. In total, these water conservation strategies save an estimated 135,000 gallons per year.

Employing a material reduction strategy: Building materials were selected for durability and appearance and many were employed in their natural state as the finished surface. The palette consists primarily of cast-in-place concrete — both board-formed and smooth surface, natural Corten steel cladding, painted and galvanized steel structural framing, corrugated metal siding, heavy dash, integral color exterior stucco, interior veneer plaster and standing seam metal roof. This integrated, sustainable and site-responsive approach ties the project to its surroundings and to its function, while creating a humane and healthy place for people to work, gather and appreciate the process of making and enjoying wine.

UCSFNet Zero Student Housing, San Francisco, CA

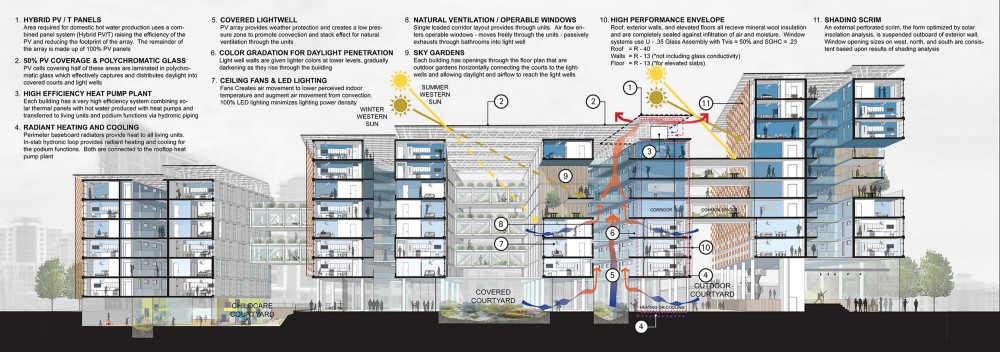

Our submission of a net zero student housing community garnered the Special Recognition Award at the 2015 Architecture at Zero design competition, presented by Pacific Gas and Electric Company (PG&E) and the American Institute of Architects, California Council (AIACC). In addition to creating a net zero facility for a specific site at UCSF, other requirements included a minimum requirement of 525 units and 775 beds as well as 19,500 sf community & support spaces, 18,000 sf Child Care and 1,500 sf UCSF Police Station.

Siting the buildings with a north-south orientation was deliberate, albeit unconventional. To achieve net zero performance, consideration of building orientation is important, but must be balanced with daylight access and solar control. For residential uses, an east-west orientation would limit direct access to daylight for nearly half of the occupants.

The ØeMission Bay design response lifts the massing, leveraging opportunities to link major green spaces to the north and south, and encourages street level pedestrian flow. Air currents across the site are directed up into the courts and light wells. The facade shading strategy is born of solar insolation analysis. Northwest and southwest facade scrims are shaped by the intensity of the annual solar radiation striking the facade. The opacity of the translucent scrim, directly proportional to the insolation intensity, allows for maximum window to wall ratios while minimizing solar gain. Smaller openings on the eastern facades are designed to reduce thermal loads. In addition, hybrid PV/solar thermal array further shades the facades and light wells.

All living units allow natural ventilation by cracking open the traditional double loaded corridor plan and introducing semi-enclosed light wells. Operable windows on opposing sides of the unit allow free cross flow of air. Light wells act as thermal chimneys, inducing convection currents upward, “pulling” air through the units. Heating is provided through high efficiency air-source heat pumps interconnected with the solar thermal panels on the roof, all of which combine to provide a very low energy solution. The podium is heated and cooled via in-slab radiant conditioning supplied by heat pumps for increased occupant comfort.

Library of Congress Packard Campus for Audio-Visual Conservation, Culpeper, Virginia

The project represents the adaptive reuse of an outmoded Cold War facility into the world’s largest archival and conservation center for audio-visual media. Through careful consideration of site, architecture, and ecological factors, the design integrates buildings into the native topography and utilizes green roofs, porous paving, passive solar planting, and other sustainable techniques to create a unique project that is finely tuned to its purpose and setting.

Background and Scope:

The facility is the new home for the Library of Congress’s Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Collections. The 400,000-square foot complex provided for consolidation of the world’s largest audio-visual collection and improved facilities for research, digital conversion, long-term conservation, and public appreciation of the collection’s 11 million items, some dating back to the original copyrights of Thomas Edison.

Adaptive Reuse:The original 128,000 square-foot bunker served as a nuclear fallout shelter for federal banking officials broadcast material. Adaptive reuse of the bunkers entailed renovation and expansion of underground and partially underground structures, including a state-of-the-art collections wing, a nitrate film wing for highly combustible materials, and a central conservation building with offices, preservation laboratories, a 200-seat theater, and conference facilities. Working closely as a team, BAR and our consultants focused on a design approach to minimize the presence of these structures and extend the subtle beauty of the rolling hills and meadows uninterrupted through the site.

Design Approach: The team clustered the building program within five of the 45 acres and configured the structures to conform to the hillside topography, minimizing grading and site disturbance. While the Collections and Nitrate Buildings are largely buried, the central three-story Conservation Building emerges above grade to provide natural light to offices and work spaces through a series of terraced concrete arcades. The building follows the slope to enclose a central lawn court which represents the project’s only formal, irrigated open space, functioning as both a viewing garden and an outdoor event space. The courtyard consists of stepped lawn terraces around a circular reflection basin that reflects the shifting cloud patterns of the foothill region, bringing sky to earth and a sense of openness into the heart of the facility. The reflecting basin can be easily covered to offer a larger useable space if required.

The arcades themselves provide a series of trellises, and the arcade beams double as irrigated, insulated planters for deciduous Boston ivy. These living awnings shade the floor to ceiling glazing of the workspaces in the summer, while in winter the leafless vines allow sunlight to penetrate deep into the building and offset energy demands.

Roof gardens cover all three buildings, masking their presence on the rural Virginia hillside and forming perhaps the largest single roof garden east of the Mississippi River. Of the total 228,000 square feet (five acres), 146,000 square feet is ‘extensive’ green roof. The ‘intensive’ profile reflects the stepped profile of the Collections Building and supports a wider range of plant material. Its depth helps to reduce cooling loads required to maintain the Collections Building storage vault temperatures.

On his design toolkit

Although I produce most of my design work with the computer, I still rely on hand drawings to begin the process and often produce sketches to explain certain aspects of the design as it progresses. I enjoy the dialog between analog and digital drawings. I often think about keeping myself honest with the precision of the computer but allowing the sketches to bring out the poetry.

In the last few years I have begun to use Lumion software in conjunction with Sketch Up and Revit for modeling. Lumion runs on a gaming engine and produces rendered environments in real time. I find it to be a design tool rather than a renderer. When I am navigating through a model in Lumion I get a visceral sense that I am in the space, mainly because of the atmospheric tools in the program. It allows a different kind of decision making to happen unlike just modeling or drawing. Although you do not model inside of Lumion, the interface between the modeling programs and Lumion is quite seamless. Other advantages of working this way are the multitude of rendered images that can be produce quickly. Experienced users can produce very compelling images without the time consuming post production that many rendering programs require. I’m surprised that more firms are not using this program.

I also use analysis software to investigate building performance. We are currently using Sefaira for whole building analysis. I’m always a bit wary while using this and keep a close connection to engineers to get feedback and insight on the results. It has been quite a challenge to get more people in the office to use it as part of their regular design workflow. I attribute that to the left/right brain divide that seems greater in designers. Many people are totally averse to looking at analytics and the back and forth from form to environmental influences that is required to increase building performance. As the software evolves, I believe there will be a friendlier interface which should make designers more attractive to it.

On the state of design software today

The pace of change is shocking. I have been using BIM for many years, and its capabilities keep expanding allowing more disciplines to participate in modeling and analysis. VR is exciting and a bit scary to me. We are just about to test some VR software and headsets, so it is too soon to tell, but I am initially skeptical about whether teams will interact well using it. It probably isn’t analogous to the impact headphones have had in separating people from one another, but I will be interested to see how that plays out. We are also researching 3D printing to see if we can benefit from it in the office or whether we should contract it out to a service firm. I’m sure it has a place in the office, but this is a large investment and needs to be carefully considered. Drones are another tool that could be interesting. Their capability to produce 3D digital imagery of existing buildings and site features will be a powerful addition to our modeling and rendering tools allowing us to produce much more accurate context models very quickly. Creating topography and existing buildings has always been drudgery for me, so I welcome the drones.

On the future of architecture in the next 5–10 years

I think innovation is needed in the graphic user interface (GUI). How we interact with computers hasn’t changed much since I started using them in the 80’s, but processors are orders of magnitude faster, the images they produce are much more vivid and the amount of data processed is almost limitless. There have been many attempts at a drawing interface with a stylus, but there seems to still be a big disconnect there for most people. It’s possible that VR will provide this tactile missing link between the hand and the machine. The other area that I think needs much more work is in prefabrication and computer driven manufacturing. This is starting to happen and it presents a tremendous opportunity to reduce the amount of waste in the construction industry. It may also offer a return to the idea of the master builder. Maybe the architect can regain some of the control that we have been busy giving to consultants, subcontractors, and manufacturers. I fear that as artificial intelligence finds its place in the profession, the human element, aesthetic sense, and empathy for the user may begin to be diluted as we are seduced by what I’m sure will be its amazing capabilities.

There will be more technology both in the design process and in construction and the linkages between the two will be closer. Schedules will get shorter due to this integration and prefabrication. More design build teams and more architects working directly for contractors.

On the future of BAR Architects in the next 5–10 years

We will form closer relationships with contractors and developers to be in a position to participate in design build, public private partnerships, and other alternative delivery methods. We will adopt technology to keep pace with faster schedules. This will include design and management software in the office and in the field. We will have to master the skills needed to produce documentation for fabrication so our designs can be used to create prefabricated elements.

On advice he would give himself

Maybe 3 things:

- Stay outside of your comfort zone, it’s the most exciting place to be

- Understand the financial structure of real estate deals

- Learn management skills