Design Manifestos: Tod Stevens of Stantec

Tod Stevens is a Principal at Stantec in the Berkley, Michigan office. With over 25 years of award winning projects, Tod enjoys the exploration of boundaries of order, scale, light, rhythm, materiality, and construction. He’s a sought-after speaker and writer on the evolving roles of libraries, and he sees every project as an opportunity to define and create a unique solution which will enhance the environment. Tod was a key part of the team that created the vision for the Mary Idema Pew Library Learning and Information Commons at Grand Valley State University. Initial plans involved a robust conversation on the future of academic libraries, and now this LEED Platinum building is receiving national and international attention for its innovative design. Modelo spent some time learning about Tod’s journey through the profession and about his current role at Stantec.

On becoming an architect

As a kid, it was never really a question for me. I remember drawing house plans for hours on end. I went to a local architecture school, Lawrence Technological University, for my undergraduate work, and completed my graduate work at the University of Michigan. When I graduated, it was a rough economic time, so I worked for a developer, which I thought that was the worst thing for my career as a designer. But in the end, it proved to be one of the best things that I ever did. I learned the politics of construction, how to strategize, budget, schedule, work with people — it gave me a strong ability to put a building together.

After that, I moved to New York and worked with William McDonough Architects, who influenced me profoundly, most notably by introducing me to sustainability. I had never heard of sustainability, and he was looking for somebody who could document a project so it worked perfectly. Literally, the guy next to me in the studio was calculating the embodied energy in a project…it made me think very carefully about putting a building on this Earth. To this day, those lessons have influenced how I approach architecture — it’s just good design!

On discovering his voice as a designer

As an undergraduate, I learned the nuts and bolts of putting a building together. We had design classes, but back then it was centered primarily on solving the problems rather than the theory or the conceptual underpinnings. My junior year, I was introduced to a Fulbright scholar by the name of Svein Tonsager, who was an influential teacher from the architecture school in Aarhus, Denmark. Svein introduced me to a new way of looking at architecture from a design and theory perspective — he literally reset my architectural education tabula rasa.

I decided then and there to pursue design theory in my graduate work and went to the University of Michigan. Their library is profound, and it helped me to continue my thirst for theory — I read everything from Vitruvius to Venturi. I was able to be in front of talented practitioners like Tod Williams, Dan Hoffman from Cranbrook, Peter Eisenman, and Michael Graves. At the time, Kent Kleinman, who today is dean at Columbia University, was one of my professors. The program gave me a rich, hands-on education in design and theory.

On joining Stantec

After working with Bill McDonough, I wanted to raise a family, so I decided to move back to Michigan. Initially, I worked as a designer with a sports architecture firm, Rossetti, where I learned how to think big and create the gesture for large scale projects.

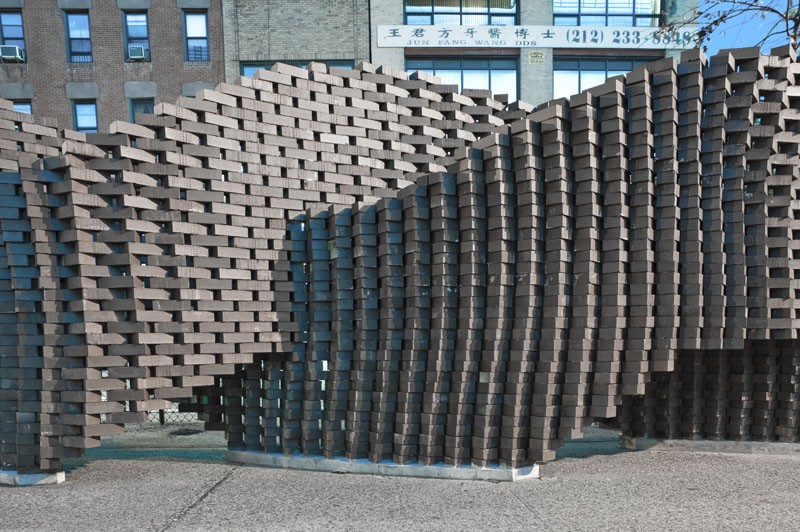

I became the Director of Design at Rossetti which positioned me years later to shift to Director of Design at Minoru Yamasaki’s office. Although Yamasaki himself had passed away, I was able to work with some talented technical architects that had worked with him. They taught me how to touch a building; how to detail exact and precise.

About ten years ago, I heard about SHW Group, a national firm specializing in education architecture that was focusing on differentiating themselves through design. I thought it was great opportunity to use my design skills, so I took a position and now have worked in education architecture ever since. In 2014, Stantec acquired SHW, which allowed our team to expand from working on tier two universities to tier one universities. It gave us an opportunity to take a deeper dive into learning and exploring the conversation on a larger scale. We are able to be positional about the work we do in education, as learning is an intrinsic goal rather than an incidental outcome.

On principles the firm strives to adhere to

Every project has the opportunity to achieve success at many different levels: success in program resolution, success in community and campus building, success in sustainability and success in creating a rich environment supportive of its purpose.

Stantec’s philosophy and methodology is focused on study, research and investigation to reveal where these opportunities reside and to ensure we achieve something important within each of them. This ambition has led us to define the ‘Five Parameters of Design Excellence.’

The Five Parameters outline how we define design excellence through Clarity, Purpose, Discovery, Performance, and Craft.

These parameters provide us with a way of organizing our thinking as we initiate work on a project, a way of evaluating progress as we work through it and a method of measuring success upon completion.

They speak to how we can approach a set of project circumstances driven by a clear idea and a thoughtful approach, and then implement a process defined by challenging preconceptions by asking the right questions, critically evaluating ideas, and revealing appropriate solutions. Ultimately, we strive to produce results that are defined by performance and craft and ensure that the idea behind a project is legible through its built form.

On his role at Stantec

Ideas are fragile, especially in their initial state. They’re vulnerable to the pressures of the world, and they’re scrutinized under so many different lenses that they can get squashed quickly. I see my primary role as cultivating an idea, and then defending and nurturing it to allow it to grow and strengthen so that others can add their areas of expertise and knowledge. You can lose a project very quickly if you lose the idea, so I work to protect it and make sure it remains legible.

I have found that one of my strong skills is to bring the best ideas out of my team. I also teach as an adjunct professor at Lawrence Technological University and that has given me an ability to move from student to student, and in the office, from designer to designer. I quickly get into what they’re trying to do, understanding their ideas and helping them clarify those ideas so that they have a strong narrative that a project team can get behind.

In the studio itself, I lead our planning, interiors and design team. I’m responsible for making sure the quality level of every project meets Stantec’s parameters.

On recent projects that represent Stantec’s unique approach

Our best work leverages the fact that we are a big AE firm. The engineers are working directly with us in real-time which is important because it can amplify the ambitions of the work. An engineer sees a project in an entirely different lens than an architect, so working in tandem helps foster a critical architecture.

For example, we designed the College of Education at Central Michigan University, which is where teachers learn how to teach. We looked at the classroom design very critically, and with an engineer, implemented displacement ventilation in the classrooms. We took the HVAC ductwork and put it underneath the chalkboard so the air comes through a wall of vents like a fog. It pillows around only in the space that’s occupied, so tempered, fresh air is brought right into the breathing zone of occupants. Because you’re not heating and cooling the whole space, energy costs are lower. Plus, it eliminates toxins in the room. In the end, it’s healthy, low cost for long-term ownership, and quiet, which makes it great for learning.

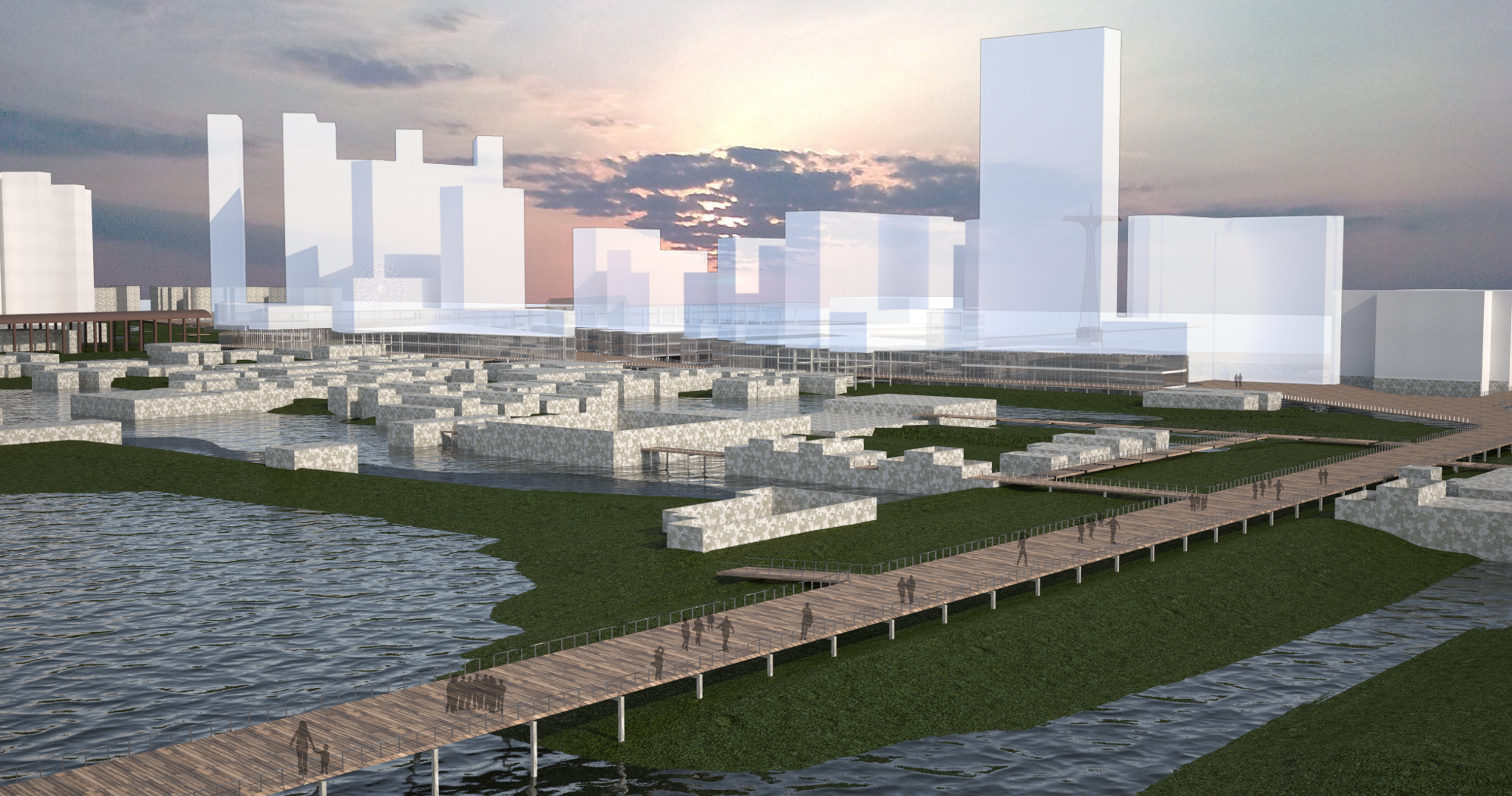

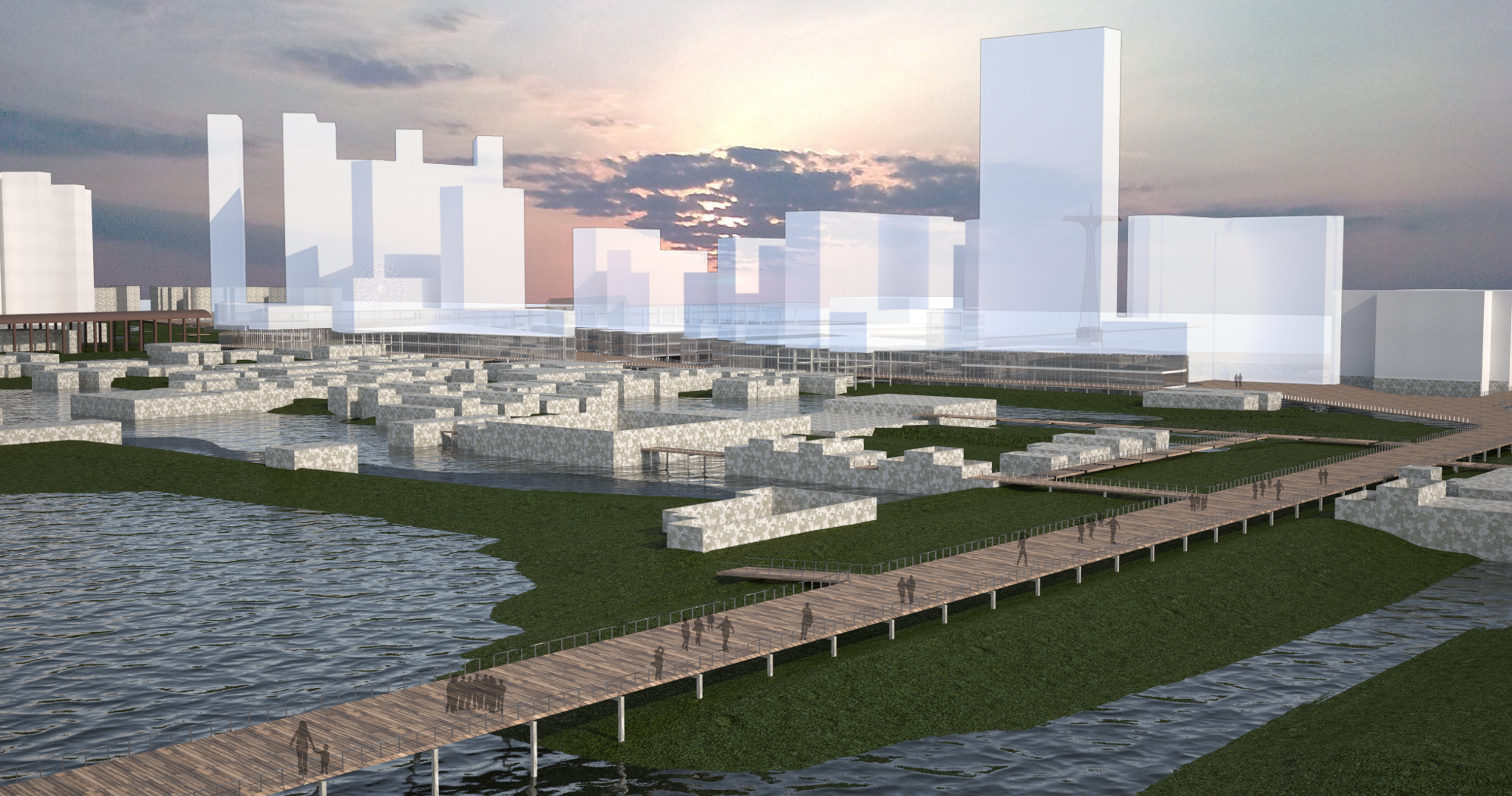

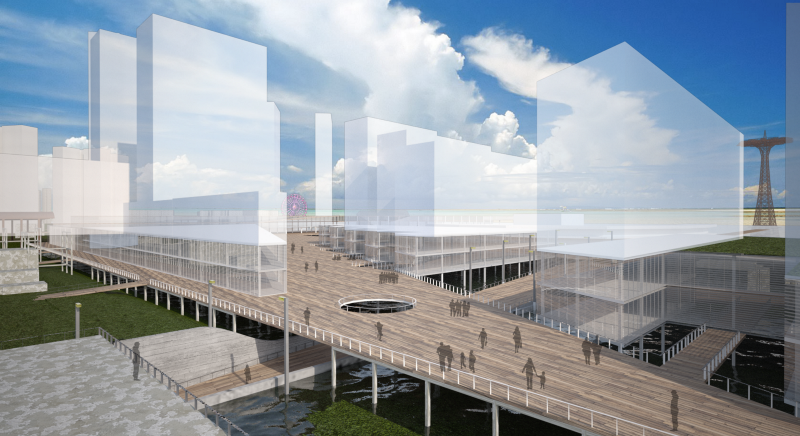

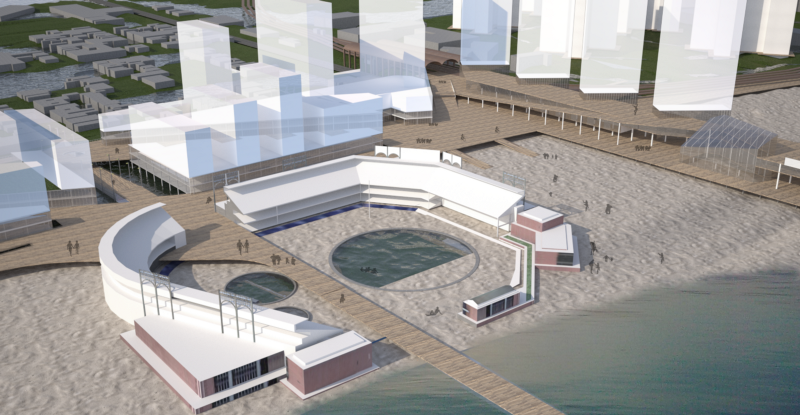

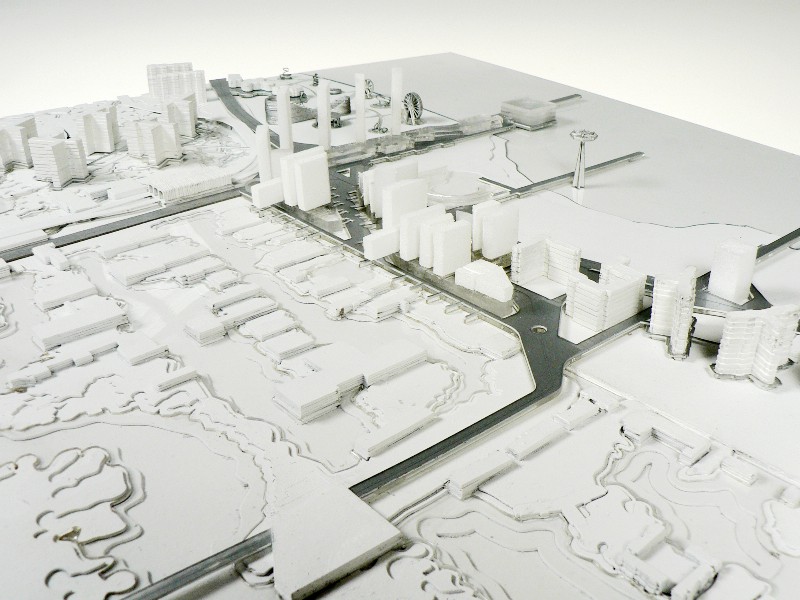

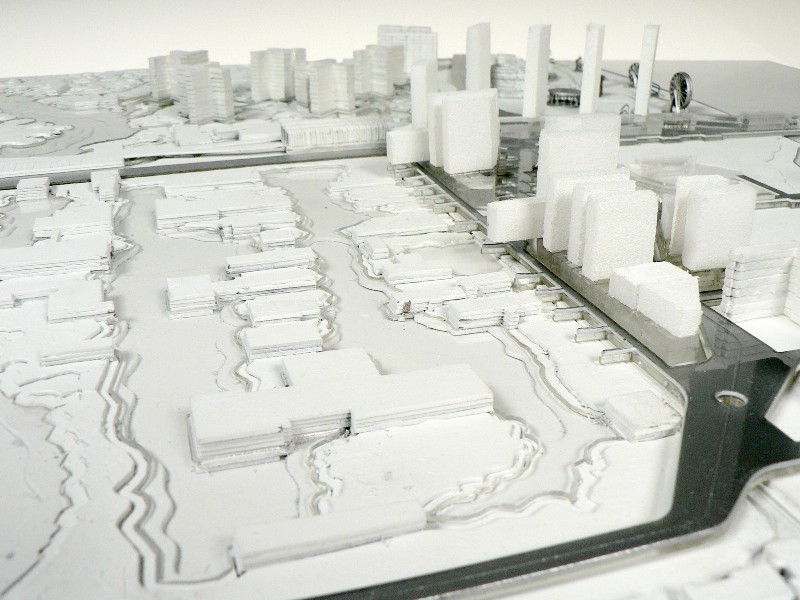

Another example is Grand Valley State University’s Mary Idema Pew Library Learning and Information Commons. It’s the longest project name I’ve ever had, but it’s an extraordinary project thanks to a true team effort — from the client to our design team to the engineers.

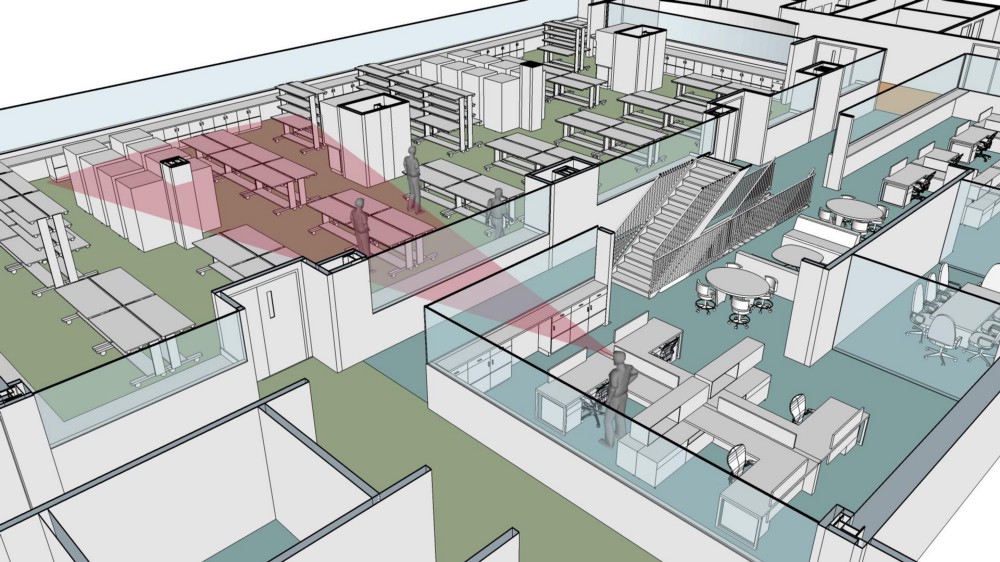

We did primary research at Grand Valley to gain insight into the way the students used a traditional library. During this time, we tested ideas by bringing in furniture and systems to see how students reacted. The successful ideas were deployed in the final building which was a remarkable moment to see everything come together and work in concert for the full building.

One thing we learned from this research was that students needed more areas for group and individual study. To free up room for the visionary program focused on collaboration, the library has an automatic storage retrieval system, which is a warehouse for books inside the library that holds 600,000 less utilized volumes in a 40-foot vault.

The library also champions peer-to-peer interactions. When you go to a traditional library, there is usually an information desk with a sign that says “Ask me questions- PLEASE.” However, it’s usually so quiet that people are afraid to walk up to that desk and vocalize that they don’t know something! At Grand Valley, we wanted to give them permission to talk and ask questions. We began to choreograph sequences to create a buzz, so when you walk in the building, there’s this amazing social space that is rich and full. We located the cafe on the first level which had sounds that drift into the adjacent knowledge market. This allows students to actually come up and say aloud, “Hey, I’m struggling with this, can you give me a hand?” It in effect lowers the threshold to learning.

On his design toolkit

Our team is strong at using software and taking advantage of the right tool at the right time. We use Revit as our BIM modeling software in our office, but we’re also old-school and use sketches and diagrams early in the process.

My rule of thumb is when you start to measure sketches, you quickly move them into AutoCAD. We do massing and renderings in SketchUp because you can do that pretty quickly. These tools help our clients understand the siting and massing of a building, while being simple enough that they don’t feel like it’s a finished product.

For a project that we’re doing for the University of Texas at Dallas, we’re moving that model into Rhino and enhancing the detailing by using the Grasshopper plugin to parametrically visualize real-time data that influences our solutions from views or solar income. It increases the opportunity for facade exploration and form — it’s powerful at this stage in time.

I can’t wait until we’re able to move seamlessly from SketchUp to Rhino and Grasshopper, and ultimately into Revit to carry the complex geometries through to documentation. There’s a little bit lost in every translation as we move from one program to the other, and I’m looking for this seamless move between those to bridge that.

On innovation and disruption in the industry

Innovation and disruption are the hallmarks of the technology world. Our occupation has been regulated and compartmentalized into the different architectural phases, and as a designer we are held to the schematic and design development phases. It’s very linear and predictable, but it’s time-consuming and wrought with inefficiency. I believe that the impact of 21st Century technology and the increasingly shrinking project timelines have created the need for us to fundamentally rethink the linear and start to seek a solution that blurs those traditional boundaries.

Instead of relying on the designer to make decisions, a strong, integrated team of architects and engineers will allow even interior designers to engage in the project rather than waiting until design settles down. In my experience, this team effort yields an integrated approach with a systemic answer rather than fitting systems and materials into that space after the “design” is done. The end result is a better project.

Virtual reality and 3D tools allow us to actually take our clients right inside our model. They give a real ability to understand the building before it’s built. That’s something that’s going to change the way we practice architecture as we move forward.

On the future of architecture in the next 5–10 years

In her poem Three Oddest Words, Wislawa Szymborska, a Nobel Prize poet from Poland, says, “When I pronounce the word Future, the first syllable already belongs to the past.” This line embodies how I think about the future. The world is moving so quickly that looking back is the trick rather than looking forward to see what is coming next. For instance, as I look back in my short career alone, I’ve been taught by architects who drew with ink on linen. I’ve migrated from drawing by hand on mylar to migrating a 2D line into a computer to literally modeling a building, embedded with all the systems. It’s an incredible progression.

The time traditional hand drawing took afforded one to think — deeply — and that time has all but been eliminated now that we are required to make decisions about how to document a project so early in the process. There has to be an intention to design all the way through the documentation. Much like Yamasaki’s office, detailing is design which can take that pressure off the early stages and really allow the idea to mature naturally.

Stantec is always evolving. In the last two years that I’ve been with the firm, we’ve grown our design force with acquisitions of very strong design firms, like SHW Group, ADD Inc, and VOA. This intentional expansion has broadened our ability to create thought leadership and design leadership as a firm. We work together and discuss how to lead the industry.

On advice he would give himself

I would tell myself to explore the world, to get uncomfortable, and to see new things. As I’ve gotten older, that has profound implications on the way that I think. It allows me to see things a little differently.

I would also say, trust yourself and your beliefs. I tell my new design staff, “You’re here because of your talent and the way you think, and don’t hold that back.” It is too easy to get caught up in a perceived hierarchy when you are new to a firm, I want their attention, and I want them to know that.