Design Manifestos: Travis Anderson of Placetailor Inc.

Travis Anderson joined Placetailor Inc. located in Boston, Massachusetts in 2012 as a Designer / Builder and now serves as Placetailor’s Design Director. In 2015, Travis became an employee/owner in Placetailor’s Co-op. Along with the Placetailor team, he has designed and built New England’s first certified multi-family Passive House and multiple other passive house, high performance and energy positive developments in Boston. His commitment to design build has led to working on projects throughout the United States, including Seattle, Pittsburgh, Brooklyn, the Yakima Reservation in Eastern Washington and hopefully someday his own backyard. Modelo spent some time learning about what inspires Travis and about his current role at Placetailor.

On becoming an architect

I grew up in rural New Hampshire in a family of self starters. My Dad had his own landscaping business and worked in the golf industry. My Mom painted murals in old New England farmhouses and had an antique store. Between watching my Mom paint and my Dad craft landscapes, you could say I was exposed to the creative process and built environment early on. I ended up going to art school at Alfred University for undergrad and concentrated in printmaking. While there, I became enamored with the process of creating and reproducing prints. Looking back, the physicality of the medium which required layering images and colors, running the presses, and experimenting with materials was very much like building. There was a base layer, a foundation, that everything was constructed off of. It wasn’t until much later, after working for artists and as a carpenter, that I realized architecture was my path. By that point I had been exposed to building and remodeling houses and helping artists realize their vision through both analogue and digital platforms. The notion of melding my artistic background with my skills as a carpenter was very enticing and I decided to apply to graduate school to advance my skills in the profession.

On discovering his voice as a designer

I attended a Yestermorrow Community Design Build course as a trial run before applying to graduate school. That is where I met Steve Badanes and Jim Adamson, both founders of Jersey Devil, and Bill Bialosky. Steve and Jim really took me under their wing and exposed me to how craft heritage and design can intersect with community, environmentalism and outright creativity. I ended up attending the University of Washington to continue working with Steve and because of UW’s strong reputation in the field of sustainable design. While there, I also had the opportunity to work with Rob Pena, kind of a silent guru in terms of building science, and learned how to calculate energy loads long hand…thankfully now we have WUFI for that. The combination of Steve’s heavy community/design/build focus and Rob’s commitment to high performance buildings definitely influenced my holistic approach to design.

On joining Placetailor

I finished graduate school during the housing crash in late 2009, so finding employment was tough. My wife and I decided to move back east to be closer to family and to be in an area where we could cast a larger net to find a job. We ended up in Boston (she found a job first) and I ended up starting my own design/build company doing additions and remodels. Pretty soon thereafter, I began volunteering with Archventures, a small community based nonprofit that worked with other nonprofits on design and construction of capital improvements. I ended up co-operating Archventures and we taught a small class at the Boston Architectural College using Archventures as a platform. Long story short, Archventures was founded by Simon Hare who also started Placetailor and Placetailor’s now Director attended the BAC… small town. When Placetailor launched Powahouse, the first multi-family passive house in New England, I decided to apply. Placetailor basically embodied everything I studied up to that point: environmental and community focus, design/build, building science and was a worker owned Co-op to top it off. To this day we continue to push the envelope as much as we can in terms of our commitment to Passive House design and construction, innovative building process and celebrating the community around our projects…I learn every day on the job.

On specific principles the firm strives to adhere to

Challenge. We typically look for projects that are nuanced and that we can learn from in some capacity. Whether it’s attempting to develop 40 units of energy positive housing, helping to train Union carpenters on Passive house construction, doing a deep energy retrofit to a community center with volunteers or finding a more efficient way to trim a window. Often times what seems like the most mundane task leads to the most creative process. Be it a formula in a spreadsheet or a saw cut, we continuously question how we work and the way we work.

On his role at Placetailor

Until recently I had been a Project Manager at Placetailor which meant I was involved with projects on multiple levels from design, energy modeling, and scheduling to running the crew and managing subs. Actual design was about 30% of what I did, a majority of the time I was on-site and in the field. As we continue to grow as a company, we have been pushing architecture more as a part of our practice. Many people still view us as the “green guys” and we want the public to realize that Placetailor is quite multifaceted.

My new role has been to heavily focus on design and bringing projects to fruition. Internally how we manage and structure the design process had been crafted over time amongst our team and now it’s up to me make sure our workflows run smoothly. We are a small company so the need to wear multiple hats is still there and I do see this role evolving some as we take on more design work and bring on more designers in the coming months. It will become more important for me to make sure we adhere to our baseline principles of taking the environment and collaboration seriously while still having fun and pushing creativity.

On recent projects that represent the firm’s unique approach

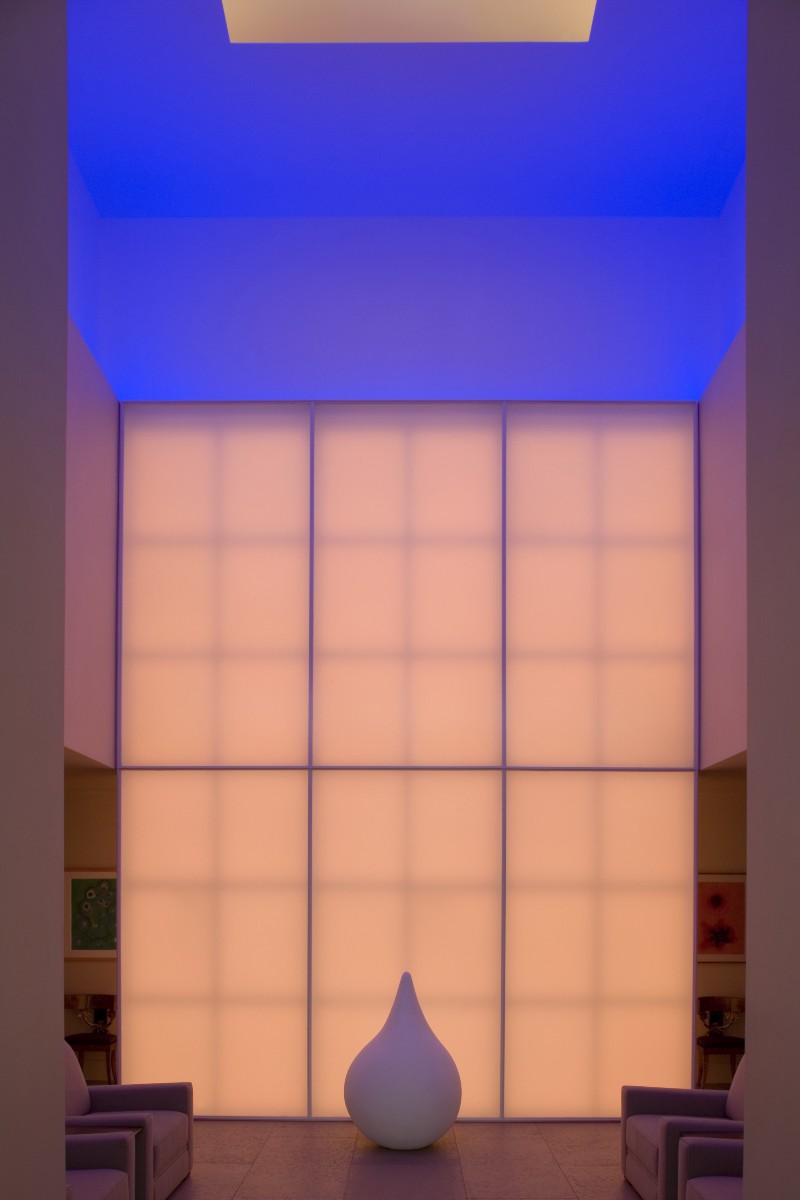

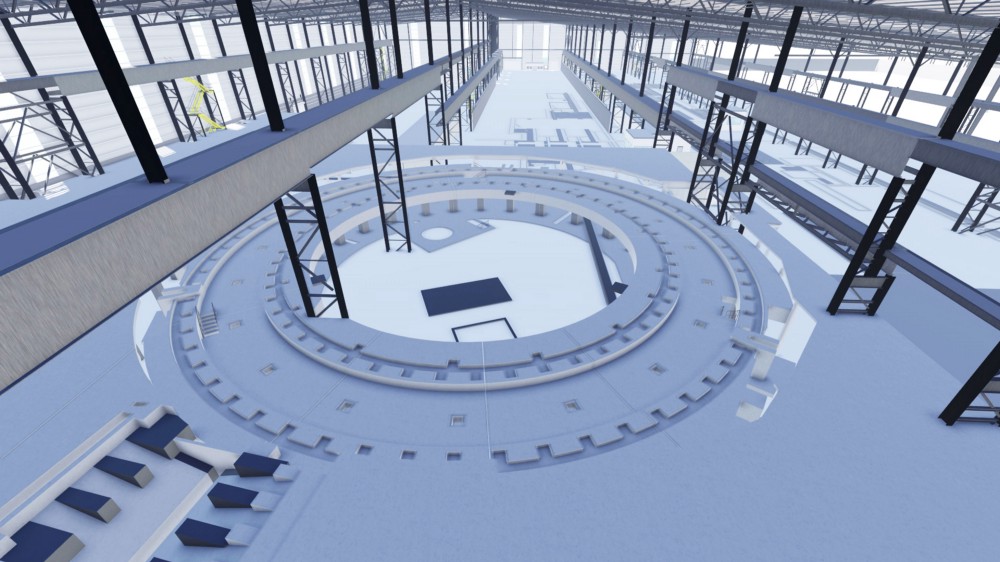

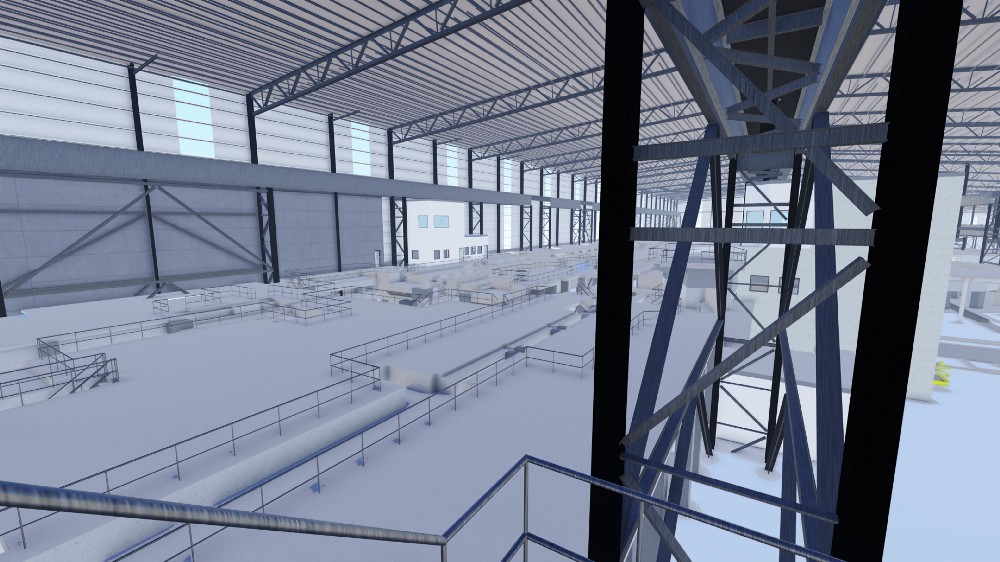

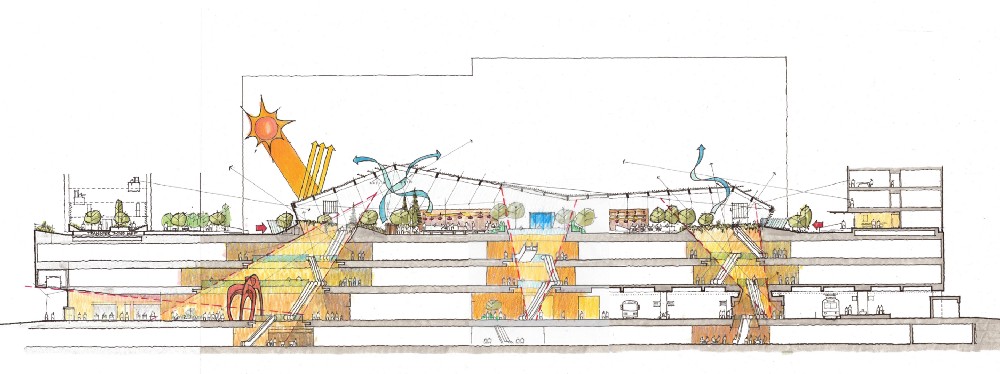

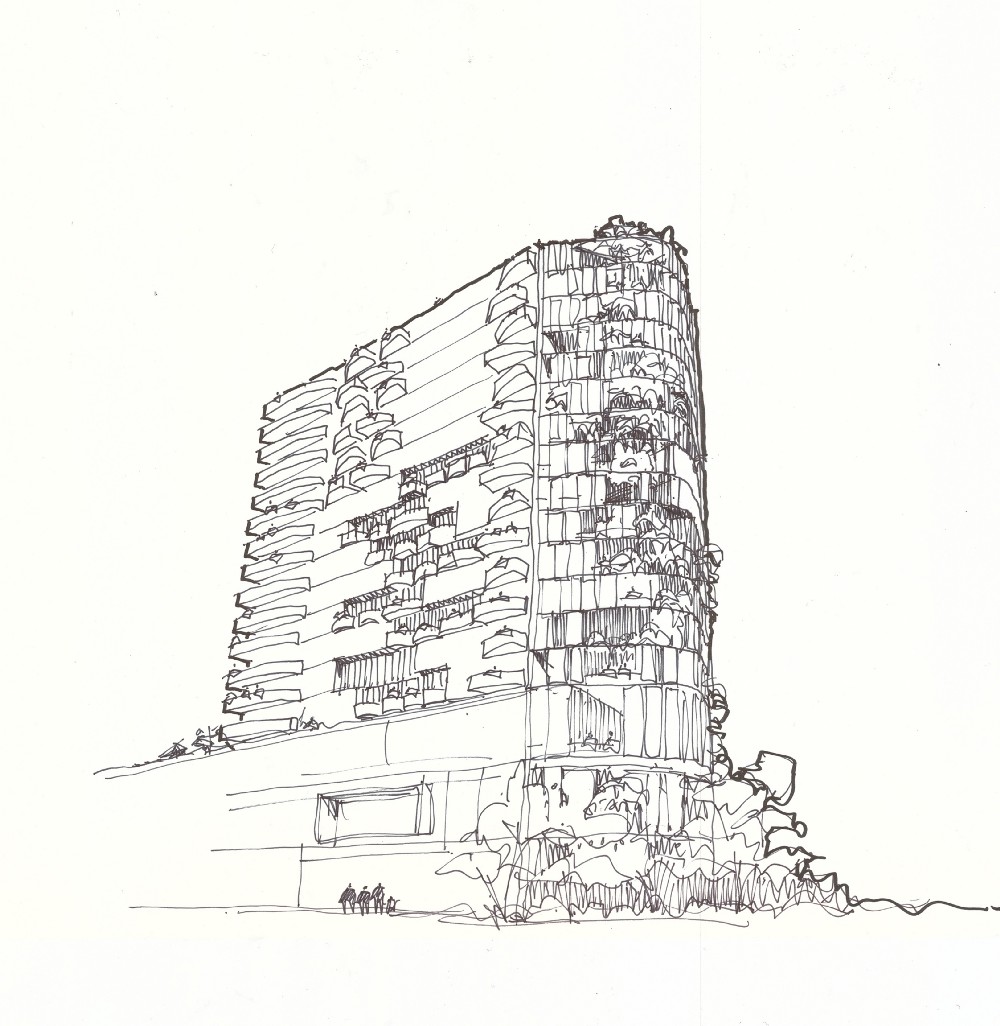

We start every project with a charrette, either internally as a team or with the community/client if it calls for it. While this is not entirely unique, what helps distinguish us early on is our knowledge of building science and background as builders that we bring to the table. We approach every project with performance, budget and site context in mind from the start. We often create the construction budget while in design development and spec materials early on as well. This ensures that we can build to our performance standards while still maintaining creativity in the design. Often times the moves are simple, like an asymmetrical roofline, window patterns or repurposing materials, but the results are often unique and generate a positive response from neighbors. We like to think of our projects as “contextual modern”.

On his design toolkit

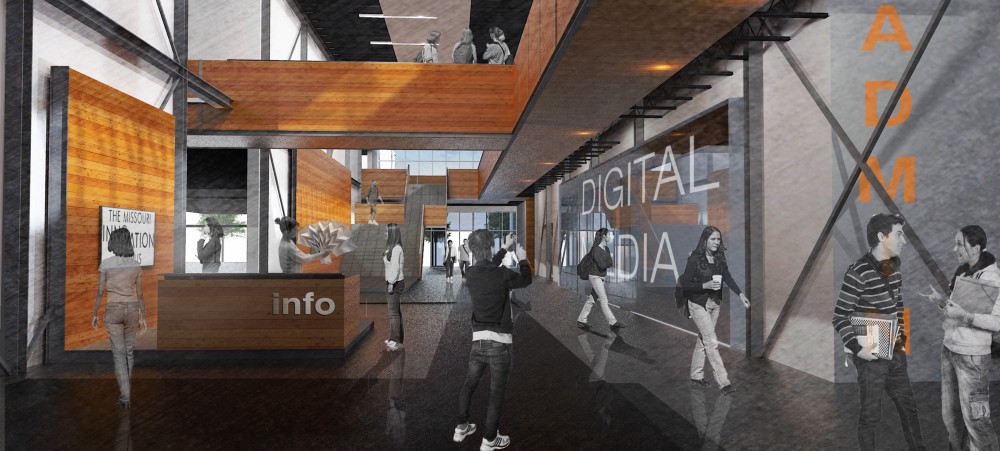

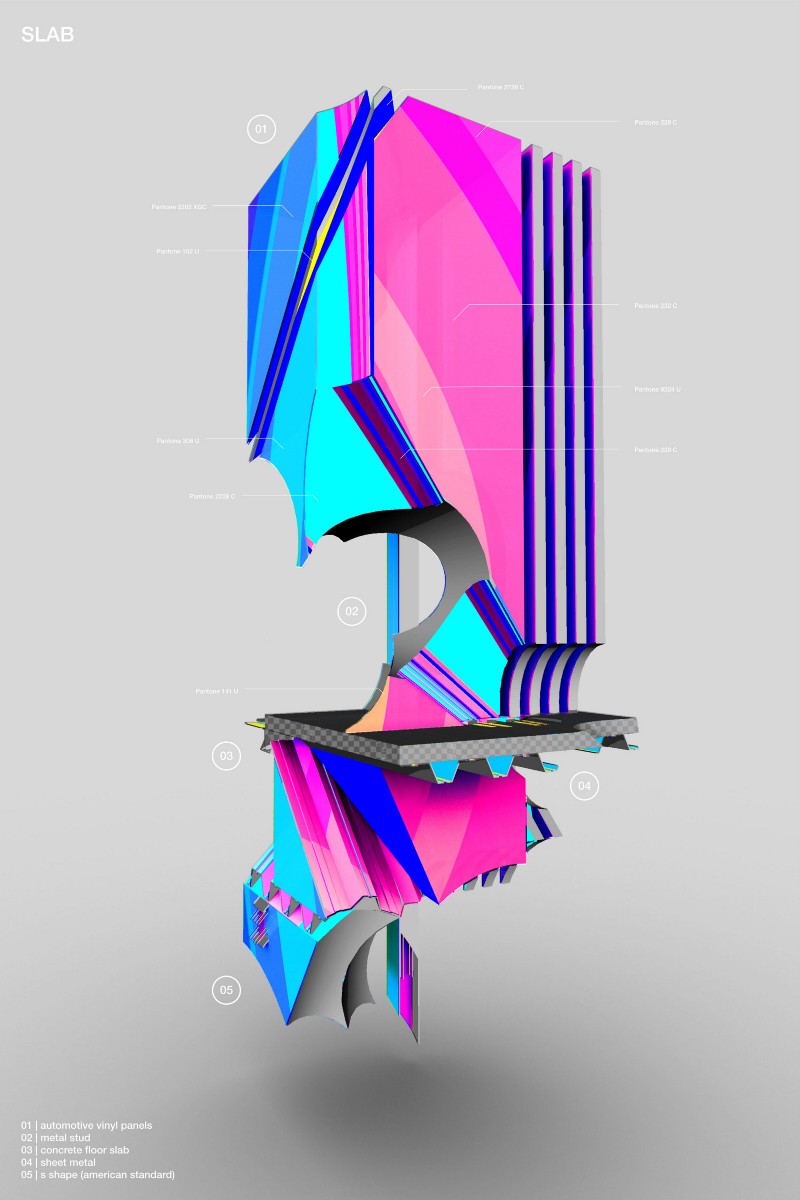

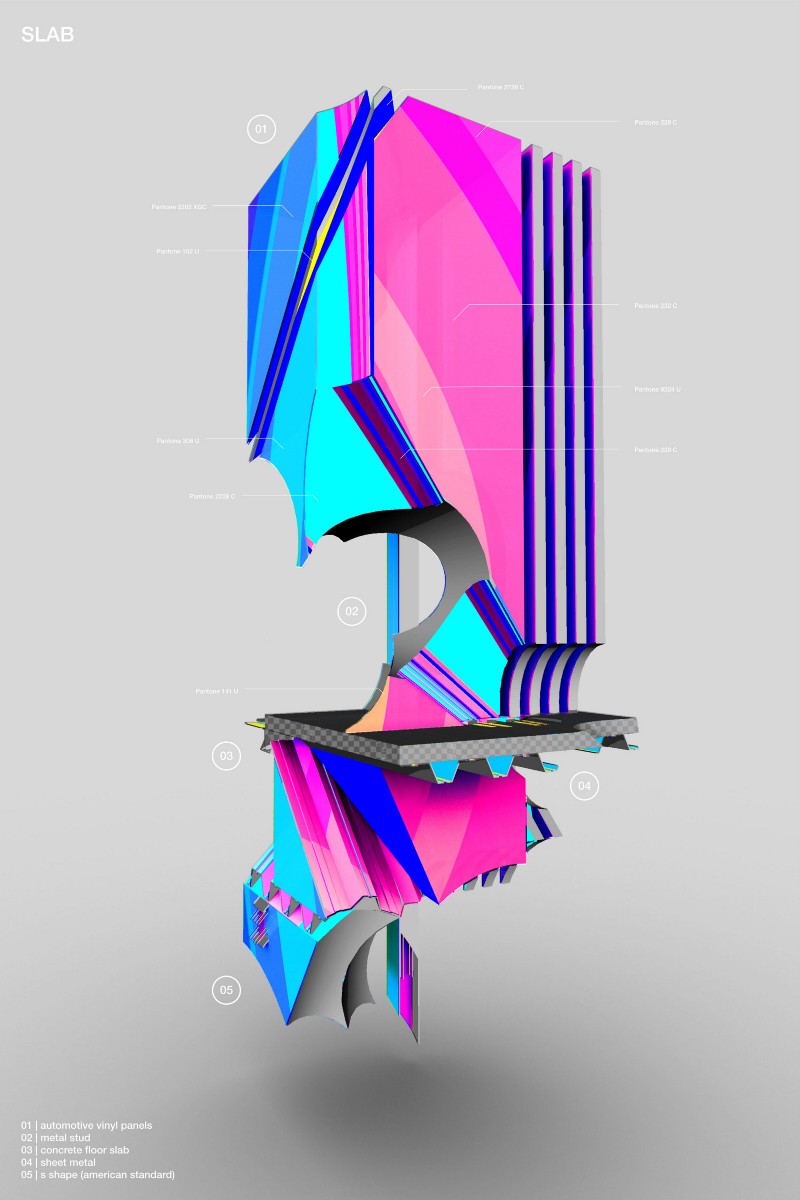

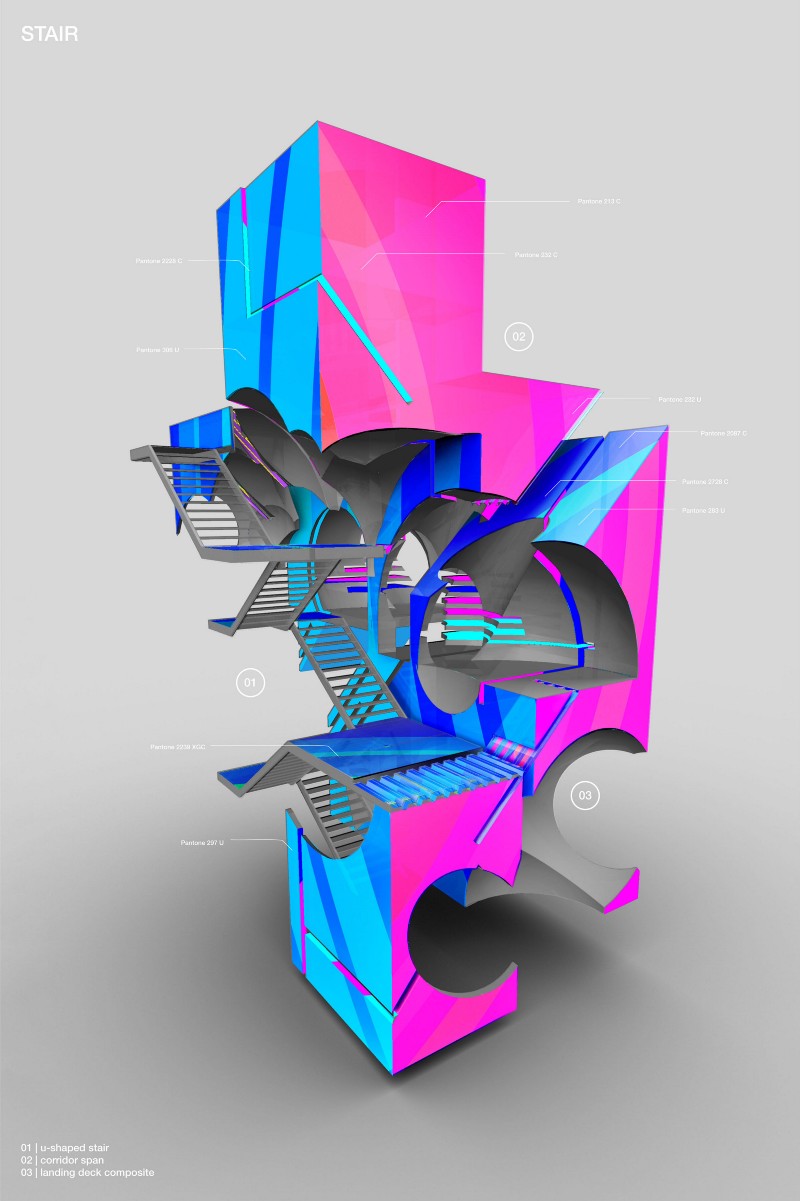

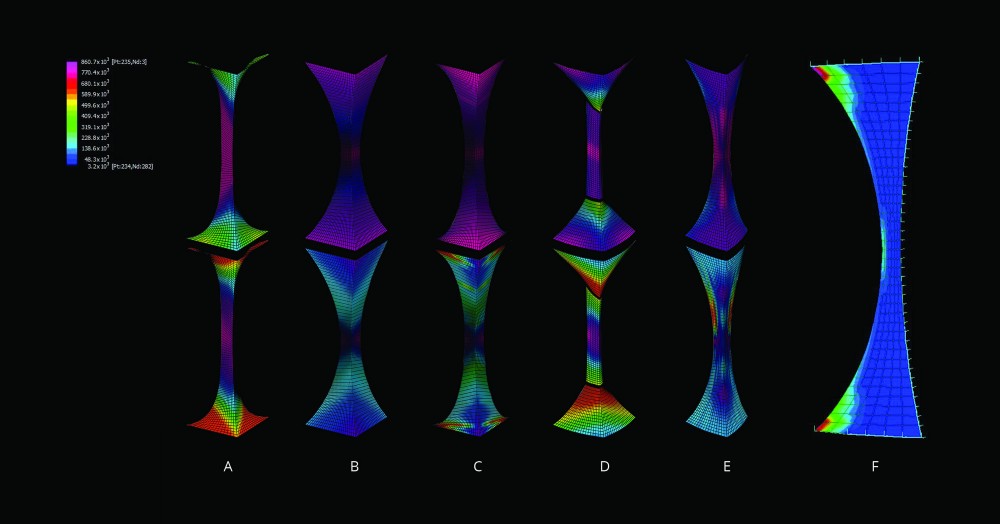

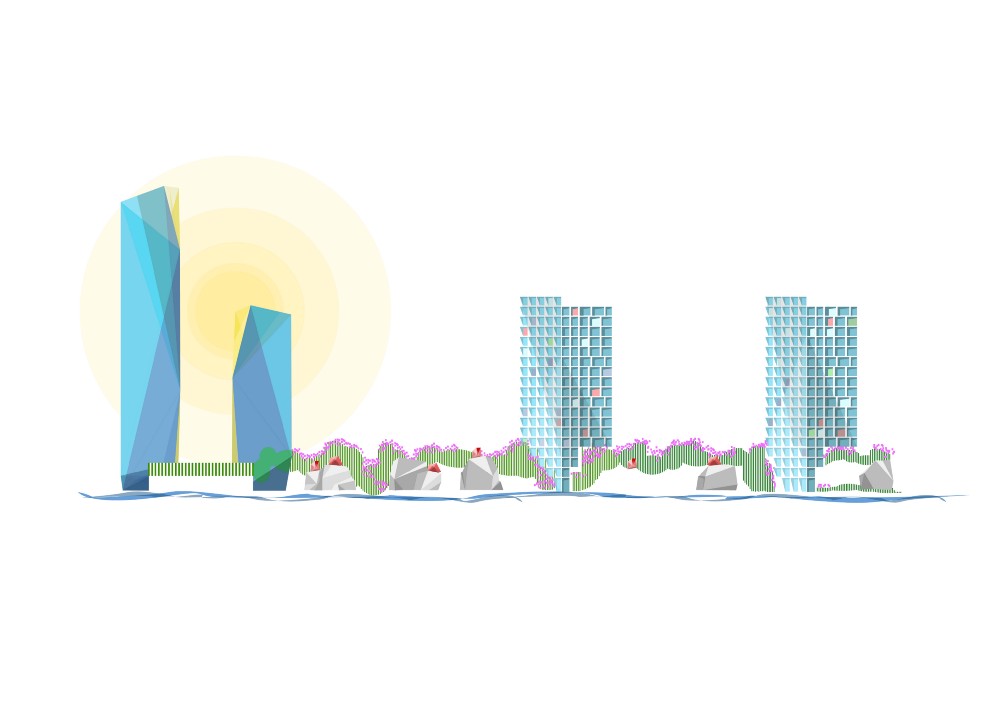

We use a variety of tools to create. We still sketch ideas by hand, but we definitely jump to revit and sketchup at the beginning of the process. That said, creating a 3D model is integral to how we work and bring projects to fruition, our work flows are very much centered on designing in 3D. When it comes to presentation we often take a step back and work more in Illustrator and Photoshop as well as integrate some hand drawings. We work directly with community groups quite often and have found a flashy render sometimes can be a turn off as many people think that is an absolute and it leaves little room for collaboration and design discussion. The 3D model also gets used throughout the construction process. As a design build company, we often are testing new details on site that continuously get added to the model. The model allows us to refine or “tweak” a detail a bit before actually constructing it. It is a nice reciprocal relationship between the site and office in creating assemblies.

On the state of design software

When I was in graduate school, SketchUp and Revit had just hit the market and you could really see the transformation in what people were able to produce. 3D modeling was suddenly becoming very accessible and the shift from 2D to 3D software was exciting and challenging to be a part of. The most exciting thing, currently, is the advancement of Augmented Reality and how that will begin to shape the industry and make architecture even more accessible to the public and other designers. As 3D and BIM modeling become even more robust and intuitive, my hope is that energy modeling software will also soon follow suite. Imagine an AR experience that allows you to see the performance of your building envelope… whether or not a space will become overheated, be too cold or not have the right air circulation. WUFI is getting there with its integration with SketchUp but it still has a steep learning curve to really use it to its fullest and I hope to see it become more accessible.

On the AEC industry in the next 5–10 years

Our hope has been that the industry will start building more high performance buildings that rely less on putting a bunch of solar panels on a project or using “green materials”. There are certainly firms out there pushing the envelope in terms of performance, but unfortunately the housing market is still saturated with builders and designers that do the bare minimum. I do think in 10 years the industry will be producing much more efficient buildings as metrics like Passive House or Living Buildings become more a part of the public understanding of how architecture can and should be. Climate change will also play a massive role in the next 5–10 years to help push more high performance buildings to be constructed. We also will start to see new ways in which buildings create/consume energy, ie. the battery backup systems for PV coming on the market. I don’t think there will be a dramatic shift by any means in 5–10 years, but I do think municipalities will start to implement and reshape policies that will push the industry toward new ways of how buildings are tied to the grid and how much energy they consume. We have already started to see this with “stretch codes” here in Massachusetts, but overall they have a long way to go.

On Placetailor in the next 5–10 years

Placetailor adheres to a triple bottom line, People, Profit and Planet, which very much informs our decisions as we look to the future. As the cost of housing increases, the next step will be making new buildings more affordable and accessible so everyone can have a happy, healthy home. I think we will start to become more involved with the tech sector in terms of how buildings are constructed and how materials are brought to the site. We have already begun to think about how a home can be built with various types of labor by partnering with Homebuilt, a “build-it -yourself platform”. We are also exploring ways in which the co-op structure can inform housing initiatives and ways to remove homes further off-grid.

On advice he would give himself

Sleep more.